Conversation with

Trevor Rabin

nfte #273

Following the conversation on Yes which comprised issue #270, Trevor and I turned to a discussion on composing film scores. Since leaving the band his film composing career has flourished, having provided scores for blockbusters and smaller films alike. At one point during this conversation he showed me a list of few dozen films he was considering and being considered for. Though I obviously didn't recognize any of the titles (as they were movies in development) I did see a lion's share of A-list directors.

Trevor is currently at the top of his profession, as well as his craft.

MOT

MIKE TIANO: When I spoke to you on the phone earlier, we were talking about my making compromises in my music, and you had jokingly said, "You should become a film composer because then you become an absolute dictator," and I was wondering if you could elaborate on that. In some ways I would think it would be the opposite, because it's kind of the rhythm of a film that dictates what you need to add to it.

TREVOR RABIN: And in fact you're right; it's a complete contradiction, because both are true, but for different reasons and in different ways. The writing of the music, I just sit here, and it's a lonely place. Everything I hear in my head goes down. I'm never stopped by, "Oh, that doesn't suit his style if you're in a band," or "I don't know if that suits that," and believe me, I love being in a band. I love that collaborative spirit, although some would suggest that I don't get involved in the collaborative spirit, but it's not true.

One of the reasons, Mike, I wanted to get into film is I grew up with orchestration and conducting and I felt for fourteen years, other than a tiny little taste of it when we did "Love Will Find A Way", where I wrote a little string piece, I think it was an octet or something. Other than that, I hadn't done anything, not really for orchestra, and I really wanted to get back into doing that... I can't remember if it was Elmer Bernstein or one of those guys said... it might have even been an agent, who said the only sensible platform for a serious, modern-day classical composer is film-scoring. From an agent's point of view, sensible in that you can make a really good living if you do it successfully, whereas if you write successfully for yourself as a classical composer, where are you going to go? Are you going to get a grant from a university to write a piece of music or whatever, maybe commissioned to do some things or you teach at a university? And that's great, and thank God for those people, but someone has to do film (laughs), and I find it such an exciting place.

A funny quote, Alex [Scott, ex-Yes manager] said to me the other day, "You said you have these songs. Why don't you finish them off and do an album, write some songs?" And I said, "You'll have to give me some footage. I can't write without footage anymore." So, if I was going to write an album, I'd need a film to write to. I mean, it's a joke, but it does get to a point, and in that way, you're certainly no dictator. It's so much more in that way collaborative, and the decision of whether the music's right or not, I think it was Alan Silvestre, who's a fellow composer and has done very well and he's very good, and he said the problem with scoring film is the best composer has to work with the worst director, and that can be true. You can be working with someone who doesn't really know what he's talking about, and yeah, you can be assertive. But at the end of the day, he can take your music and put it there, or put it there, and luckily for me up to now in the twenty-odd movies I've done, every single piece of music has stayed intact and it's stayed where it was meant for.

I've felt sorry for James Horner, who did "Titanic", who wrote to the picture and James Cameron didn't even consider where it was put. He would take it and just put it wherever he wanted, and that's one way of doing it, but I would be kind of in hell doing that, but I've been very lucky working with some great guys: Jerry Bruckheimer's an unbelievably smart person-clearly business-wise, but also creatively; he's very smart guy. He sometimes gets a bad rap because every movie does $150 million, very rarely does he have a miss, and it's kind of lonely at the top kind of thing, he makes movies for the masses, but they know they're no less valid for a composer. I think my theme for "Armageddon" is one of the better thematic moments I've had in a movie. At the same time, I think "Whispers", which went direct to disc was also one of the best moments; but I certainly think, as a whole, I've written my best music with film, definitely not in a band or as a solo artist. It's been with film, and I don't know what it is. I don't know whether it's because part of your brain if preoccupied with the job at hand, you've got all this stuff to take care of, and so the side of you that creates the music is more unconscious and you're less conscious of what you're doing, because the minute I start thinking about writing, it's hard. If it's like dusting the room and that's how I'm approaching writing, it's when the best stuff comes through.The minute I try and push it, it doesn't happen, and that's why I think film's been good for me, because I'm concerned about, "OK, I've come in at the wrong frame. It's four minutes, thirty and eleven frames, it needs to be twenty-eight frames at thirty frames a second, so twenty-eight frames going to be best because his head's turning, and OK, I've got to come here, and I've got to change to a fifteen-eight bar here because that's in the way, and then we've got a transition. I've got to come down a little bit, a bit of a descresendo here, and then I've got to go far more allegro in this part, and then go to seven-eight bar... " So when I'm preoccupied with that, the actual melodies and stuff have to be kind of almost second nature, and I don't know if I'm making any sense, but it's a much more flowing kind of experience. I mean, twenty movies is twenty albums; I've done like twenty albums.

MOT: Any forced venture is not as creative, or as good as when it just comes from inspiration.

TR: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. I've had some nightmare moments on film, and some on what I consider the best scores I've done. One was on "Deep Blue Sea"; I was so happy with it, I thought, oh God, if I pass away tomorrow, I'm kind of happy. Now in retrospect, everything I listen to is, "No, no, I can do that again. That's not right, that's not quite right," everything. But the director-a lovely guy, Rennie Harlan from Finland, just a wonderful guy, just loved him, and he said to me, "I really love it, especially once you integrate the shark theme onto this." Well, this is the shark theme, and this is forty minutes into the score. So I had to kind of integrate a new theme that he was going to like, but into all of this because there's no way I could rewrite it all, and so it was a full week, and a week in a movie is like, it's getting closer to the dub, and you can't hold it up. I've got orchestra dates set, well over a $100,000 a day for the whole thing, and I can't just say I'm not ready, like a record. "Well, I didn't feel creative today; I'll get back to you tomorrow," it's not the case. You've got to perform; you've got to get it done, and I was like "Oh my God!" and I stayed up for twenty-eight hours straight just pounding away and nothing happened. My fingers were bruised as I was playing the piano and I was literally frazzled... and then it just came to me. It was just a simple little melody, and I put it on and said, "Oh, it works great." I had to manipulate and change some of the stuff, but what it did was it improved the score. The score went from here kind of to there, so it's one of those... it wasn't intentional. It was not contrived; there was no desire to try and do something different. Those are the best moments, so I don't know.

When I finished a song that I thought was good, I thought, I don't know where that came from, so I have no idea if I can do that again. I'm talking like, a hundred and fifty songs down the line. I still feel that. With a score, I've got to the point now where I'm so confident that's it going to come that my terror, which happens before every film, is much less than it used to be, but it's still there, because the expectation is, "We need this, and you must not have heard it before. It's got to be great, and we want exactly your thing, but take it a step further," and I said no problem. But when I finish a film and I'm completely spent and exhausted from it, and I'm starting another film a week later, it's like you've got to get up and run again. It's amazing discipline, because I can procrastinate, and I can do a song. Look at BIG GENERATOR, I mean, the reason that took so long was it was part of where the band was at the time, but it was also partly my fault of hopefully being somewhat of a perfectionist or trying to be-taking too long to do things, and with film...

MOT: You've got a hard deadline there, and money's on the line.

TR: Exactly, and you have to work, so the idea of being that spoilt, you know, being a spoilt rock star-that's out the window. It's like, deliver, and it's a much more realistic kind of environment. I don't know, I might change back into my old bad habits, but I think if I go and do an album now, I think it's going to be a thousand times better than anything I've ever done and more together and with so much more soul and feeling, because that's one thing I've got, and one thing I look at when I listen back to what I've done with bands. And I'm talking about even Rabbitt, which is many, many years ago. I really look at it and think, "You know, people should be crying at this point in the song. Why is it not doing it for me?" Because so often you think, "Well, it sounds great, the snare sounds good in this. Wow, look at the difference, the interplay with the instruments. You're in this time signature; I'm in that one, and we're working against each other and we meet again here." But what is it emotionally doing and sometimes that kind of, I think generally with a lot of bands, and Yes being one of them, sometimes the emotion for me was not left out of it, but needed to be considered more-from my point of view, I'm not talking for the other guys. So I think when I next do an album, I think it's going to be from the heart and emotional point of view. It's going to be a different thing; you know, I'm a different guy now.

MOT: Your point is well-taken in terms of context of the music, because moving to a theatrical metaphor, people don't leave the theater humming the lights.

TR: Absolutely, exactly. You know one of the things that I've been forced to learn is music is the emotional voice of the movie, the emotional color of the movie. Denzel Washington is an amazing actor, and it was so easy, once I got the melodies and things right on "Remember The Titans". I actually got cold shivers when I got it right and it was agreed upon; that's the other part of the collaboration of film. If you think it's good and finished, it's not necessarily so. I mean, once you develop a relationship like I've developed with Bruckheimer and a couple of guys, then it becomes a little more like that, but for the most part you've got to learn yourself first, learn how the other guys work, but it's feeling the emotion. What music does to film is amazing. One thing, I'm actually doing is, I'm doing the NBA theme for TNT.

MOT: Oh really?

TR: Yeah, and that came about because this guy Craig Berry is his name, wonderful guy. He had edited "Titans" into the end credits of the Olympics which was used on the Olympics, and I actually got a tear in my eye when I saw the Olympics because the music just worked, and I just knew it was going to work when I first heard about it, but they'd said yeah, they're going to be using "Titans" for the Olympics. I just knew; I said well, that's going to work fine, because emotionally that's one of the strongest scores I've done, so yeah, I think it's one of the things that's so important with film, you're the emotion.

MOT: As far as the NBA theme, are you replacing the (sings a few bars of the current theme)?

TR: No, that's the NBC theme. No, it's moving from NBC, so they're also going to be redoing their theme. But TNT came to me first and whoever's getting it on network hasn't come to me, and TNT has been pretty smart. They've said it's exclusive; in other words I can't do, if ABC comes to me, I can't do one for them as well. But I've agreed, because it's the right people for me, and I've never done anything like that before.

MOT: You're absolutely right about how the score's so important. There's nothing worse to me then watching a movie and thinking about the score. I don't want to be thinking about the score.

TR: Absolutely.

MOT: When you go back and look at older films, scores were used kind of sparingly. Now, sometimes they're overused. I hate watching a movie where there's nothing but music where it detracts.

TR: I've got to tell you it's so funny, because this movie I'm doing right now, they wanted wall-to-wall music, and I couldn't help myself. It's a Bruckheimer movie, but it was with the director, and I said, you know what, even in a wall there are windows, and sometimes you need to open those. You don't wallpaper over your windows, and I think that's the biggest problem with film right now. It's too loud; the effects are too loud. The picture's incredible these days, I mean what they can do with film now is quite extraordinary. I'm doing a comedy I'm thoroughly enjoying called "Kangaroo Jack". It was called "Down Under", but now it's "Kangaroo Jack". And it's not real, the kangaroo, it's all CGI. It's unbelievable what they can do, and with music now, because of the state of the art of fitting things in, with the 5.1 [surround].

I just did the "Armageddon" ride for Disneyland in Paris, which was unbelievable. I'm working with dozens of speakers, and one of the first things you get is the schematic of the speaker system, to know how to write for it. There's so much outside of rock and roll that is so much more advanced, who would of thought a theme park? They are so advanced when it comes to sound; it's extraordinary. I went to Paris, because I wrote the music, and the guy-he was actually here this morning having a meeting, brilliant guy by the name of John Dennison-he said, "I think you need to come to Paris," and I said "Why? Is the music wrong?" He said "No, but I think you need to come to Paris," and I said, "To listen to a missed cue?" He said "Listen to it in the environment," and I went there and I completely re-wrote it. As I heard it, I said this is the best move, you don't even have to do it for me, and they took me through the whole ride, and it's "Armageddon"... it's a $150 million dollar ride or whatever it is-millions of dollars involved, and there's going to the space shuttle, and there's asteroids hitting it, and you're falling. It's unbelievable-so I don't know, I'm getting off the point here, but just film and even outside of film, there's that kind of area.

One thing I'm not interested in is commercials, because that's just not for me. But film is I think an extremely creative thing. I just worked with a guy on Bruckheimer movie, called "Bad Company" with Anthony Hopkins and Chris Rock, and Joel Schumacher was the director, and he's brilliant, and there's just a sophistication to the thought process, which I just enjoy. I played him a piece of music against the film, and it was definitely a little too busy, but he didn't say it was too busy. I said, "What do you think?" and he said "Have a look at it one more time, but trust the film." Things like that makes so much sense, because they're poignant, and they make you think. It's not like, "Don't put that there," it's not that kind of "Duh" kind of thing. It's like it's thought-provoking, it's, "I want you to think about what I've said. I don't just want to be literal and say do this-do that, because I'm not a musician; I don't know, but I want you to just take what I say and translate it into whatever you have to hear what I'm saying and do something with it." And I came back and played him the thing, and he just hugged me, so I love that about the film. There's smart people working in film, not all, but a lot of smart people-creatively smart people as well. That's the people I like to work with.

MOT: (laughs) As opposed to creatively dumb people.

TR: Yeah, or as opposed to smart business people, I could care less about them.

MOT: True. I'm sure that's probably one of the daunting things about the film business, how the whole business side of it can be a little baffling and intimidating.

TR: Oh yeah, yeah. But it's funny, I'm not as cynical about the business of film as I was about the business of rock and roll. When an A & R guy would say to me-I remember Derrick Schulman-he was the singer of Gentle Giant, and he started over, he took over Atco Records when Yes were going to do an album after BIG GENERATOR, and I'll never forget meeting him. He said "I know exactly what you guys have got to do, and it's right there. You got to take what you did on FRAGILE and CLOSE TO THE EDGE, but lead it with what you've done on 90125, and it's really straight-forward. It's a formula that'll work." And I was so angry, and I thought, "You asshole!" I couldn't help it; I was so angry, and we're sitting there, and I said, "Well, you do it. I don't know how to do that, so you do it, because I don't know." You know what I'm saying? These formulas for making big rock and roll records, and I think that's why the whole band, because everyone in Yes, in different varying degrees, are creative people and honest about what they doing, and that's why I don't think they liked it, because it was definitely business people thinking they're real smart.

I was very cynical is what I'm trying to get to, and our guy's saying "We need the single," and I'm saying, "Well, it's not ready, what do you want to do?" "Well, just give us a bit... ," "It's not ready. I'll give it to you when the last coat has gone on." It made me angry; with film, it's a different thing, because there's more at stake financially-usually, anyway-and you accept some of the business parameters, and when you see a guy like Jerry Bruckheimer who's so creative and so talented, and he doesn't direct and he doesn't write music and he's not a cinematographer, and he doesn't do casting, but without him there overseeing this stuff, none of that stuff would be what it is. It's kind of like Trevor Horn; I've heard some people-and I defend him heavily-a lot of people talk about Trevor Horn and say "Well, he's as good as his engineer," and I couldn't disagree more vigorously, because if you put Trevor Horn with that engineer or that engineer or that engineer, somehow it always sounds like Trevor Horn. There's always Trevor Horn stamp on it. You take that engineer who's successful now because of Trevor Horn, take him out, and it doesn't sound like Trevor Horn anymore.Getting back to the point, a guy like Jerry, he deals with the business, and he doesn't see it as being evil or ugly, it's what you have to do, and I mean I know there's some really ugly parts to it and parts which drive me nuts, but not in the same way as music business.

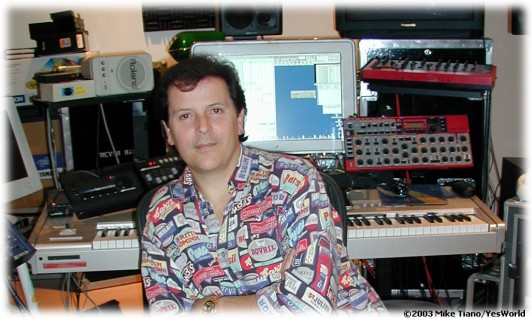

[At this point we took a short break while Trevor demonstrated some of the work he was doing for "Kangaroo Jack".]

MOT: One question that popped up while I was watching was, do you play on your own scores?

TR: That's all me, yeah. In the old days, you know the first score I did, I was nineteen years old, and I just finished kind of selling this brilliant guy Walter Monies-orchestrator, conductor, professor at University of Johannesburg, brilliant guy, he's a Canadian-and so when I did the first score, I was with Shelly-[BTW] we just had our twenty-third anniversary, wedding anniversary-but I went with paper and a pencil and a projector with the reels and a piano, and away we went on a holiday and I wrote the score, just write it to paper, go in, say to the director, "Ok, this is kind of what the trombones will be doing." You play the piano, and those days are over. You now have to mock it up, and depending how far you want to get, if you want to get into things like "Fargo", which is a very sound design kind of score. It's different, but if you want to get into scores overall so you can do that, and you want to get into scores which are orchestral, you need to be able to run an orchestra in your studio, and so I play every part, and once it's past, this stuff just gets typed, put onto paper for each instrument.

MOT: You were saying earlier that you're basically writing a demo to the film?

TR: Right. [But]... not always; because sometimes, quite often, the demo becomes the movie because the director will prefer that version to what lands up on the orchestra, because it's identical note-wise. It's the old thing; if you're a keyboard player and you have great string sounds, a real great violin sound, if you don't understand voicings and harmony, you can have the best string sounds in the world and they'll just sound like someone playing chords. It's got to be voiced obviously, so having the right sounds and voicing it properly makes a huge difference,

I'll play you a piece which I wrote for a film, which I'm actually not going to do, hasn't worked out schedule-wise, but "Pirates of the Caribbean", was a film I was thinking of doing and looking to do, and I actually wrote the demo for it, thinking it was going to be a kid's movie based on the ride, and so I wrote that and my imagination just led me in certain ways. The sounds that you can get now, you've got the play them. You got the put them in and understand the instrument; you can't just play an oboe sound and think it's going to sound like an oboe.You've got to understand how an oboe works and be able to manipulate it with the technology for it to do that. You can use an oboe sound; it'll sound nice, but it won't be an oboe. You have to understand the instrument, have studied the instrument to a degree, just to at least know.

I mean, even practically speaking; [like] a clarinet. There's an overblow; you get (imitates a clarinet), and at a certain point, you breathe harder to take it up, so you can't just keep going, so you've got to take into consideration the overblow, and if you don't do it on the keyboard, then the arrangement's not going to work if you can get it to the real people. So it's tough, and it's time consuming, but these days you have the luxury of performing it as the orchestra's going to sound; it might not have the dimension, but it's pretty damn close, but you don't have the luxury of just writing it out and not worrying about those things because you naturally will write them in the right way. But when you've got a clarinet, which you can play anywhere on the keyboard, it's like well, the clarinet can't do what you playing, so you have to understand what the clarinet can do in order to make it real, practically real.

MOT: Do you get a rough cut of the whole film before you start the composing process? Or in a more general sense, can you give us an overview of what happens?

TR: I'll give you an exact example. What happens is I watch the movie, but first I read the script, then if I like the script, and then I'll meet with the director. If we get on... or in the case of Bruckheimer, yeah you're doing the movie. [But] I read the script first, and if it interests me, and it would interest me in a number of ways: who's the director, do I know who the director is? Oh, him? Oh, this movie's perfect for him; he's going to make this look great. How's the script going to be? Well, he's not great with script, but it doesn't matter on this film. You know, I've just done a movie called "The Banger Sisters", with a first-time director, but the scriptwriter is Bob Doleman, who's an unbelievable scriptwriter. He's probably my favorite scriptwriter, so with that, it's down to the script, and I'm reading it, and it works. He's been involved enough to know how to shoot and the film looked good, so there's varying different ways of assessing whether it's going to be the right thing to do.

MOT: I would think one of those would be whether you think you could bring something to it.

TR: Oh, that's first and foremost. If I think it's going to be a great film, but I'm not quite sure what to do with it, I'll ponder it maybe for a while, but if I still don't come to terms with it... I mean, I actually I was going to sign on to a movie-I'd rather not mention what it was, but a movie which I actually signed onto, and after seeing it-and not because it wasn't good, it was a great film-I just decided, I can do it but it's just another project and I've done this before, and for me to do this, I've really got to go back to what I've done before, and I might be happy to do that at some point, but I'm not now, so I'm wrong for the film. So that's happened as well.

Once I've established whether I want to do it or not, which is based on those kind of ideas, then usually it's read the script, have a meeting, and they've got to decide... you can have a meeting, and they say he's an asshole, and that's the end of it, but I've had good luck with that. I haven't had any people saying, "I hate his guts," it's been very nice on that level. Then I get a real rough cut and I'll watch it, and I'll watch it a couple of times. Usually what I do at that point-which I don't know anyone else who does it, I don't know if it's right or wrong, it's just what I like to do-I like to just keep the film running while I'm writing, trying to get some thematic things going, and some orchestral style, stylistically trying to find out where we're going. Sometimes it's not even orchestra, like "Homegrown" there's no orchestra on it. There's dobro and pedal steel; it was a guitar score. "Titans" was almost exclusively an orchestral score. "Jack Frost" was exclusively, or one or two queues was a bit of rock and roll. So I'll watch the movie, and I'll write some themes and play the themes, "What do you think?" "Oh, I love that theme, well, that one I don't know," and I'll write a little more, and if he doesn't like the theme, I'll put it aside and bring it back and say, "What do you think of it now?" "Oh, now it makes sense," or maybe not, it depends, but I always write something to start a dialog.

It also helps because once you've done that, and you've got a theme established when you start putting it, they recognize it, as opposed to just starting cold, so I usually write three or four minutes, which I've done with [his demo of] "Pirates". And that's happened as well, where I've written themes and there's a couple of movies where they've offered it to me, and then decided not to do it, even though I've written a theme that I think is strong. Once I've written that suite, then we'll do what's called a spotting session, where I have a music editor who works for me. What the music editor does is make up these charts, and what they're basically based on, and here's a summary of it. This is... it's a very small score; it's not very long, but this is basically the score.

MOT: To be clear, this is everything that you've done?

TR: This is the movie; this is the Kangaroo movie. No, this is the list of stuff I'm going to do, because what we do is we have a spotting session. What we do at the spotting session is we decide where it's going to go. I'll say to a director, "You really don't want music here. Let the crickets be the music. You're at the lake, let the water and the crickets be the thing. Let's hear some dogs barking; leave music out. Maybe I can bring a harp here and there, or maybe I can bring in a whatever, but let's not have a cue here." You know, slide something in halfway through, so whatever the case may be, we decide where these things go, and this is what we landed up with on this movie.

MOT: So this is the plan, basically?

TR: This is the plan, and then what happens is I say to the music editor because we now know the movie, "Just create some, for identification purposes, what one and nine is. Ok, it's the warehouse chase outside Sal's," so that when we say one and nine, the director says, "Well, what's one and nine?" It's only relevant to me. I can tell you, you can take this, and I can tell you after a week working on it what one and nine is, because I know it back to front within a week.

MOT: Like a song title of sorts.

TR: Yeah, so I know what one and nine is, and the funny thing is, I've had twenty one and nines, because I've done twenty films, but when I'm on the film, I know exactly what that is. I can tell you from previous films what one and nine was, but so you have one and nine, then you go to reel two, and you carry on. Well, this is the way I do it; I carry on with the cues. I don't go two and one, two and two, and then three and one, because sometimes two and one will land up ultimately on the first reel, then what does it become? One and what, eleven? It's much better if two and sixteen becomes one and sixteen, because there's one and fifteen.

For example, here we end it one and eleven, right? So, instead of going two and one, because it's the first queue on that reel, I actually go two and twelve. Do you see what I'm saying? It's just library work.

MOT: It's just the number, like that's the actual number of the cue.

TR: Exactly.

MOT: In sequential order, starting reel two, number one.

TR: Exactly...and then here, this is what I'm provided with for this fifty-two minute score; it's not too bad. Then you get to the specifics. OK, one and one is source. It's the Zombies' "Time of the Season", so I just need to know that, I'm not going to do anything with it. However if the song is used, I have to make sure key-wise and everything if I'm overlapping, that my transition is in the right key and is intact, and it doesn't rub against that the wrong way. I don't deal with that until the end, because nine times out of ten the song changes. And there's ways, you can use musical gymnastics where you can take a key from here, which is so completely different to hear, and with a bit of transition, you can move it into here fine, so there it is, one and two. Segues from one and one, on dissolve to beach; segues to one and three... music plays, Louis is introduced, and continues as Frankie sends Charlie out for a pass. Note: this could be Louis' theme. The little notes that we've discussed, and that goes throughout, and there's just pages and pages of it, and that's the film. That's basically the whole film.

I just find it's fascinating, some people have come to me and said "So, do you write the music afterwards, and how do you get in onto the tape?" Well, you go to a huge dub stage, you go to massive orchestra and then to a massive mixing stage, and like rock androll where you might be mixing at best a 5.1, that's about as big as you get. With film, I'm mixed at 24 tracks. That's the mix; you need 24 tracks to play it back. And the reason for that is because you need to maybe send them to different places, so I've got 275 channels here of board, and rock and roll is 24, maybe 48 channels, and you've got hundreds of channels of music, and you're mixing all of them, and it's like I've got to knit certain things together, so this percussion is going to be knit, but I mustn't knit that to it, because that's going in the subwoofer track, and that's got to go to the back, and that's only going to be in the front, and when the Foley comes in, it's going to be hitting there, so I can't worry about that, so that's got to be on a different track. It's so exciting to me, this, and the actual music is just something that I do by the way kind of thing, and consequence or the result of that is that I'm in a Zen place at all times with the music, because I'm not thinking about it.

MOT: I'm glad you brought up the Foley track, because do you find yourself involved in other parts of the sound design of the films, and the Foley track, depending on what the sound effect is, could be part of the orchestration. [The Foley track contains sounds other than dialog and music, like footsteps or traffic.]

TR: Oh, absolutely. Depends who it is. A guy who I've worked with seven times, a guy by the name of George Watters, who won an Oscar last year for "Pearl Harbor"; he's, in my view, the best in the business in sound. That's a guy who you can go to and say, "Look, I'm doing a cue on this. What kind of frequencies are you looking at for blah blah blah?" That's when you can really talk... there's some guys who just don't really understand it in the same way. A guy like George Watters you can go in and say, "What are you thinking?" "Do you think you can give me some space around like 1 K, just give me some space there?" And it's not even about EQ, it's about what the nature of what he's going to put...so those are the kind of guys you can talk to, and there's a lot of them. And then some guys are very good but are not interested, it's just you do your score, I'll do my sound design, we'll fight it out on the stage, because if you think this is a lot, when you get to the dub stage--have you been to a big dub?

MOT: No.

TR: The board is literally from that wall to the other wall, and there's hundreds, there's probably a thousand channels. You've got 24 tracks of music; you've probably got 24 tracks of sound effects. You've probably got 6 tracks of dialog... so there's a lot of guys, and then you have a music mix on the stage, you have a Foley mix, and you have a sound effects mix, and a dialog mix sometimes, and it's four guys, and then there's usually one central guy overseeing the thing, then there's the director overseeing the overseer, and there's the producer overseeing the director, (laughs), so it's cumbersome. But when it works, it's like a beached whale-when you get it in the ocean and get it swimming, it's glorious.

MOT: What scores do you feel are your strongest? Which ones work the best for you?

TR: Oh, you know, there's actually a lot of them that I'm real happy with, and I'm not talking about even just for a movie, I'm talking about when I'm done and gone, the things that I hope my son will listen to, will be "Whispers", which is a movie that was barely released. "Armageddon" was the biggest movie that I've done, so I have affection for that because I was kind of happy with the themes. I think "Armageddon" would rate up there, although I definitely think "Jack Frost" is one of the stronger moments. "Remember the Titans" I think is definitely one of the strongest scores I've written. As far as orchestral dexterity or prowess or whatever you want to call it, I think "Deep Blue Sea" is probably one of the stronger moments.

MOT: Do you find writing a score that uses more of your guitar playing talents is more enjoyable? Like maybe on "Homegrown"?

TR: No, no not at all. Not at all. Because the guitar is just an instrument now. Before, I was the guitar player in the band, now guitar's a color on the palette; it's just another color, which is ironic because as far as being a guitar player, I think I'm better now than I've ever been. I know I am.

MOT: Which film composers, living and/or dead, were an influence on you?

TR: Ennio Morricone, that's probably my favorite. He did "The Mission"; that was a wonderful score. I think that's my favorite. I mean, there's a lot of good guys around, but he's my favorite.

MOT: One of my favorite films where I think the score was definitely a contributing factor is Alfred Hitchcock's "Vertigo".

TR: Oh yeah, who did that?

MOT: Bernard Herrmann.

TR: Oh, well no, I humbly apologize, because he's without doubt, the icon and my favorite.

MOT: Oh really?

TR: Oh yeah, of course. That's why "Vertigo", it's like-he's the king. He's the guy; he's the godfather. I mean, I was almost taking it for granted I'm thinking about the guys today. No, he's like absolutely. Brilliant, absolutely brilliant.

MOT: This is self-indulgent, but how do you feel about "Vertigo" and the score in relation to that film? You are familiar with that film?

TR: Well, the thing about "Vertigo" and how it paces with the film is it helps the film. It's doesn't just sit, I mean there's not much score, compared to today's scores. Right, would you agree with that?

MOT: Well, there seems to be quite a bit there.

TR: There's more than in the older, older days, but what I was going to come to is the balance; today's scores which are wall-to-wall and the old scores which was nothing. Even some of the worst scores, like take... and a wonderful composer Lalo Schifrin I think did it, who's a great guy-"Bullet" with Steve McQueen; it's a horrible score, but it's not because of the music, it's horrible because of the time. It really wasn't understood... I think the direction was bad as well, but you know, it was a learning process. But there's a film where, boy did it need some more score. It was so lacking in score; there was nothing there, and then you get a movie like "Gladiator"; it's just wall-to-wall-to wall, and it's like "Oh my God, shut up for five minutes!" And some of my movies, I want to shut up for five minutes, but even in places where I've said, "I'm not going to do a cue here," they've convinced me, because as I've said earlier, I've lucked out in that I haven't had a score where I've written there, and put there... so "Vertigo" I think, and I don't remember it vividly, but I think it's an unbelievable movie for one thing.

MOT: I recommend you watch it again soon!

TR: I am going to watch it, but what I vaguely remember is that the balance of the score-to-picture I think is right.

MOT: With that I agree. My comment wasn't in terms of there's too much score.

TR: Oh, ok, because I definitely don't think there's too much, but I don't think there's too little.

MOT: Herrmann was definitely a pioneer, all the way back to "Citizen Kane".

TR: Well, he kind of started the real deal kind of scoring. He's the guy.

MOT: So can you talk about the projects that you have upcoming at all, on the record?

TR: Actually, there's nothing I've actually signed onto for future right now, partly because I'm trying to keep myself reasonably free, because I'm possibly thinking of touring on the live album. We're talking about it; I had a discussion with Lou today on it-the drummer from the CAN'T LOOK AWAY album, the tremendous drummer, and I've got two movies coming out, so and I haven't had a break. I just haven't had a break for a long time.

The good news as far as progress is that the list I used to get was six or seven, and out of that six or seven I'd be asked to do three quarters of them, and then last year it was maybe ten movies, and I did five, and two I turned down or three I turned down, and then two which I would have been happy to do, they chose somebody else, and that's going to happen. I'm not right for every film that's for sure, but with that, it's the same kind of scenario, but where this is at is this is the list the agent brought to me, and this is the short list, so I'm on the short list of all these movies, so it's probably two other composers... in fact there's no more than four composers that are being considered on this, and it's not on there, but the email I got from them highlighted all the ones that I'm absolutely the front runner on, and that's how it works. So there's fourteen, fifteen movies I'm front runner on that list, and then a lot of them I'm strongly in the running, and then there's a whole list of things that I don't want to do, because it's B movies or too much violence, or... gratuitous violence. Some people don't mind, I'm more picky.

MOT: So you do take content under consideration when you're choosing a movie.

TR: To a degree, I mean, a movie like "Gone In Sixty Seconds", there's big car chases, and it's like, well who cares, I mean guys get slammed over the head with a baseball bat, there's a level long before that that I won't do. I certainly won't do any porn. And I'm not talking about porn movies; I'm talking if there's a scene which is...

MOT: Gratuitous sexual content.

TR: Yeah, kind of anal sex with a donkey and the movie's with Anthony Hopkins; I'm still not going to do it (laughs).

MOT: (Laughs)

TR: That's a funny thought, isn't it? (laughs)... so yeah, but I'm not too fussy. I think people have got to look at movies as being entertainment, and sometimes thought-provoking, and if there's some ugly parts to it, well maybe it's suppose to be and it doesn't matter. I don't think Ozzy Osbourne is the reason for all the bad on earth. Apparently Rick tells me he's a wonderful guy, and "AC/DC made my son commit suicide"-I like AC/DC, and it's not what I enjoy to play, but it's fun, so same thing with movies.

MOT: It seems like more and more rock musicians are being asked to write scores for movies.

TR: Yeah, and that's not right. When I say it's not right, I don't want to put myself out of a job, but I don't think it follows that they're going to do a good job. I think thetemperament is so different, person-to-person; it's weird that I fitted it into it; in fact the engineer who worked with me on TALK, Mike Jay, when I said I'm going into film-he worked in film a lot, he said, "Don't do it. You won't deal with it," and I said why, and he said, "You'll kill the director after a day. You don't compromise, you're not going to put up with any of that." So he thought I'd be completely wrong, but I do think it's relevant to a lot of people.

So I've been involved in that side; I think that's an important element to have. If you're going to go and do a movie or two, like a "Fargo", it's sound design, or Ry Cooder does some scores, and he does beautiful scores, but is he going to go and do "Harry Potter"? I don't think so. What it does is if there's a rock and roll guy who can do scores, there's an added interest. It's kind of sexier to the film company's for some reason, and I know the first couple of scores, that's how I got into it. Yes is not relevant in people choosing me. It was in the beginning; "It will be quite sexy. He can orchestrate; he can do that. He does film; we like the way he does it, and he's from Yes. It will be quite kind of cool."

MOT: Well, you can cross over to the other side; I mean now they probably say about you, "Well, he's done 'Armageddon'; he's done 'Enemy of the State.'" I mean, those are some pretty heavy hitters. Yes is kind of irrelevant in that context.

TR: Exactly, but I mean there are guys who I really respect who are very good musicians and whose albums I liked, who turned out to be a disaster when it comes to film. Todd Rundgren did a score for "Dumb and Dumber", I think, and I didn't really mind it. I don't know what they were complaining about, but apparently it just wasn't quite what they were looking for, and there's an understanding. It's a psychology; you have to get into the mind of the director. You can't anymore be the only prima donna; you can't be the only one who's un-together and, first of all, you can't be un-together. This is not that kind of job; you have to be completely together, organized-very different kind of job. You can be a prima donna to a degree, because that's part of how you get things going. I know that, and I've learned enough about myself to know a bit about that, that I have that tendency--not as much as some people I know, but some directors do, and you have to deal with them. So it's kind of a weird dichotomy, but you have to deal with it. I've grown up as a person in the last five years more than in the last thirty-five, forty.

MOT: It's interesting about the prima donna aspect, because going back to Bernard Herrmann that's one reason he and Alfred Hitchcock split. Do you know about that?

TR: I don't know the story.

MOT: Basically, he did the score for "Torn Curtain", which was your basic, traditional Herrmann score. It was a movie with popular stars, Paul Newman and Julie Andrews. Alfred Hitchcock came back and said, "No, the film company said we've got to make it something more popular." This was in the mid-1960s where hit singles were coming out of the films and Herrmann said, "No, forget it, I'm not going to do it," so Hitchcock went ahead and got somebody else to do the score.

TR: Wow! I didn't know that.

MOT: Speaking of Hitchcock, his last film "Family Plot" is an example of a score that doesn't fit because there's this underlying harpsichord kind of a half-amusing theme that goes through it, but I thought it undermines the film.

TR: Oh man, that can happen so often. You cannot be a bull in a china shop when you're doing film. You also can't hold back when it needs for you to just grab the screen and throttle it, you know? It's like NASCAR, and it's a very different world. For example, John Williams-great composer, did "Harry Potter". Everyone hates the score. Well, I saw the movie expecting to hate the score, and all I hated about the score was that it was mixed so loud, that's it so in the way of the dialog. No matter how good the music would have been, you just want to get rid of it, because it's just in the way, and you got to be able to turn it down, and if it's still in the way, take it out. Do another cue and have the guts to say you know what, it was what you were saying, don't put one there, leave it out. And I fight for that all the time, because the music would be so more poignant and reasonable, and reasonable is a better word conceptually to put there if it's preceded by silence.

MOT: Is the volume for the music in your control?

TR: Oh no, not at all. The dynamics, and I'll play you this thing I did for [the "Pirates of the Caribbean" demo] and you'll see there's a lot of dynamics, but when it comes to the final dub they've got these explosions going on, and then it's like you turn it down, and it's got to be replaced by something, because it limits it. I mean, it's like driving a truck in some of these movies, some of these action movies particularly. "Banger Sisters"-very different themes, very controlled and subtle and it's all about the dialog, and those are really fun when you're writing dialog with music. It's really fun. But a movie like "Armageddon", it's like (mimics an explosion). There's a space shuttle, and Ok, I have to get the world anthem out at the same time... I said to Jerry, "Ok, what are we doing for this?" and he said, "World anthem, it's got to be the anthem of the world," and that's how I wrote "Armageddon". I don't know if that's the anthem of the world, but it was certainly my brief.

But in order to pull that through, it was like (mimics explosions) and then as the jets fire, and then visual can take over and let the music play (mimics heroic anthem), so it's pull and push, and boy do they pull and push. You do your best; the best compliment I ever got was on that film "American Outlaws". The mixer said to me, "It's kind of an Aaron Copland-ish kind of vibe to it," and I love Aaron Copland, so the mixer came to me and shook my hand and he said, "It's one of the first movies I've been able to just leave the music sitting there, and it just rides it." And I said, "That as much a compliment to you as to me, thank you," most of the time it should work like that, but things get pushed to such an insane level that you have to push the music for it to work, because the dynamic range that I'm working in is here, which is substantial, but the movie's like that, so I have to compensate sometimes.

MOT: When the movie is finished and you go see it in the theater with people, how do you gage whether you've been successful or not?

TR: After about a year when I watch it on my own, with a DVD.

MOT: Really.

TR: Yeah, just sitting back. When I go to the premieres, I can't hear it; all I hear is "Oh God, oh God, what did I do that for?"

MOT: Being self-critical.

TR: Oh, completely. I don't even see the film; I don't even know if it's working with the dialog when I go to the premiere. I have no idea. And then I'll hear something like, "Oh boy, that's working great-turn it up! Why did you put it so soft?" So I'm mixing it in my head, and there's so many aspects to it which I'm working at the premiere, and then even if I go to the theater, I don't go anymore to see the movie in a theater. I used to think it was fun to go and see the movie in a theater; I don't bother anymore, because there's usually a guy throwing popcorn down the back of my head. So I wait for the DVD, but you know when I watch the DVD with Shelly or with my son, then I can hear if I've been successful or not, in my mind anyway.

Notes From the Edge #273 The entire contents of this interview are

Copyright © 2003, Mike Tiano

ALL RIGHTS RESERVEDSpecial thanks to Jen Gaudette

This conversation was conducted on August 22, 2002© 2003 Notes From the Edge

webmaster@nfte.org