Conversation with

Steve Howe

nfte #250

When I visited Santa Barbara in early April of 2001 Yes were laying down tracks for MAGNIFICATION, their first album without a fulltime keyboard player. The album was to be augmented by an orchestra, which would cover the string parts that in the past had been created by Mellotrons and synthesizers.

At this point in the sessions there were no orchestral tracks, only the raw sound of the band. But even at this early stage the songs sounded crisp and vibrant, and what I heard reminded me of KEYS TO ASCENSION II. Coincidentally KEYSTUDIO, the compilation of the studio tracks from the two KTA volumes, was about to be released in the UK. In light of the similarities in the members' working dynamic it almost seemed appropriate.

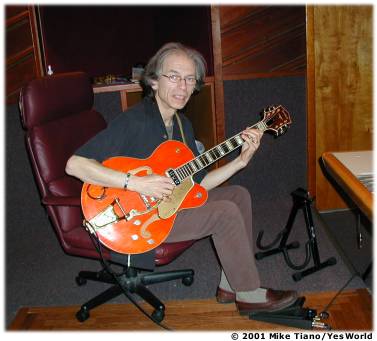

Steve was in the midst of another creative stretch, just coming off of his first acoustic album, NATURAL TIMBRE as well as working with Oliver Wakeman on 3 AGES OF MAGICK. We discussed these activities and other subjects on an evening off from recording the new Yes album. -MOT

MIKE TIANO: How did the idea to do an orchestral album come about?

STEVE HOWE: Yeah, it was certainly convoluted. Here's the short version of the convoluted story, if you like. Ideas for different Yes tours, annually it's a discussion-how we're going to tour, what we're going to do. Of course now that we're clearly four people, we've seen that one option that we've maybe had before, but never been closer and about to realize it, is that we're going to tour with an orchestra-a different orchestra every night in major towns, major cities. So that came about through the kind of tangents and talking, discussions about different things that we would do, but mainly it came about because actually it possibly suits us perfectly at the moment; we're without a keyboard player, and we imagine that the orchestra would take on keyboard parts.

So we met up with a guy called Larry Groupé, who works with the San Diego Symphony, and we started to talk to him about this project. Initially he was very excited about doing the old music, and we have a time frame

where he's going to set about doing that old music for an orchestra, to play every night, and he will conduct it. We will go on tour, and he will conduct a different orchestra in different cities, playing his score of Yes while we play. It seemed to me that since we were looking for an orchestra partly in place of a keyboard player, I suggested one day, why don't we do that with the record; instead of having a keyboard player, why don't we use real instruments when we want them, if we want strings, why don't we have real strings. So the penny dropped, but much like I told you the story earlier about Les Paul and the other innovators and the people who dream up ideas, there's a lot of other people who actually help you get there, so in my small way thinking of that idea-I don't take total credit for thinking of the idea of putting the orchestra on, it kind of came through discussions, and I kind of noticed that was an option; and when I pointed it out, the guys said, well that's a pretty good idea.

Well, suddenly it's grown almost larger than life (laughs). The reason it's larger than life might be said that it's become a realizable option that we've got. In other words, there's Yes-four guys experienced together-suddenly projecting a different side, leaving a different gap in our spectrum of sound that isn't filled up, but it's then allowed to be filled by an orchestra. So, what are all those samples on people's records, they're samples of parts of an orchestra in many of them, so we're really bringing live music, we're bringing real people again and again we're bringing real playing to our music; less sampling, less programming and sequencing, you know, none of that at all, so we're proud that we made a record with an orchestra.

TIME AND A WORD was a similar experience-a record I'll never cease to find the opportunity to mention that I love very much, because I think it's a terrific record, and Bill plays his ass off on that record. So Yes have encountered it once before my time. I will confess to some tremendous excitement on hearing some ideas, and then some concern that we decide how much this thing is going to operate with us, how much this marvelous, tonal reality... and having just done an acoustic album I know that I'm kind of finding that I am a bit of a purist inside of me.

MOT: You're a purist in so far as-

SH: Well, I'm saying that in my recent experience time and time again, all the things that I thought were modern and hip and you could plug and make it sound like things are not a waste of time; but they just filled in a time when I had to go that way to get that sound. But when you want real sounds, you don't fantasize about what's impossible, you create fantasy out of what's possible, which I think is a wonderful thing about music, is that we're all so affected by electronic music, but still we wouldn't even be here if there wasn't acoustic music, because when the power goes off, man...

One night I was playing a solo show, I think it was the first night in Argentina I ever played, I was playing in Cordoba, a lovely place, but anyway on opening night and in the middle of that show the power went off, and of course I had an acoustic guitar, so I didn't carry on, I stopped and thought, Jesus, I'm in the dark and nobody can see anybody, and then I just started playing something else that seemed to suit that moment if you like, just took the moment and went, wow, and I played Bach in the dark (laughs), and I'll never forget that. It's like Yes has always said, if the power goes off, it's a drum solo. Why do you say that, because it's an acoustic instrument, idiot, for why do I ask the question-it's so obvious, but it isn't thought about in those terms enough I don't think, but when it comes down to it, when you cut all the fuss and paraphernalia of modern life, you know you have an acoustic instrument, and you play the thing-it's great.

MOT: Do you find the logistics of having to perform with an orchestra to be daunting?

SH: The round stage was just a brilliant idea, do you know what I mean? When I stepped on it, I thought, oh dear. This is not what I thought at all, it's a new experience And the few times I've gone onstage with an orchestra, and I have been just a couple of times, it does do something pretty weird to me, I got to confess. I hoped that it's going to be a very enjoyable musical broadening. I don't know if it's going to be, but I hope it's going to be, that's what we're all hoping it's going to be, is a broadening of Yes sound into, if you like, going back to my beliefs, maybe that simple is always better, real is always better, acoustic is always real, so therefore it's always better, so this marriage might work very nicely. I'm going to still play my 175 and my other guitars; it's not that I'm going acoustic so much, but certainly having real people playing real notes in real time might be a nice, exciting thing.

MOT: Let's back up to the actual recording of the current album. I'm interested in how you see the orchestrations coming into some of the music.

SH: We've been working quite closely with Larry Groupé, that in a way when he does what he does, it will have our blessing. It will have each to our own satisfaction look through that score with him, make comments, and something that we feel must be seen through, and so maybe some harmonic simplifications might happen in some places where he doesn't come in so soon, because we're already happy. I like this band; I like this band a lot.

MOT: So, let me be clear here: is Larry the one writing the orchestrations to what you're doing?

SH: Yes.

MOT: In other words, you're not giving him a score or melodies and saying, "We want to hear this... "

SH: We're giving him tracks to listen to. We intend to work more closely with him to create the kind of arrangements that we believe in. But we're not writing them. He's inventing them, and then we're having the chance to stylize them if we find that they might be overzealous or they're understated, whatever way that it falls.

MOT: I was wondering whether you were actually writing out a score for him.

SH: None of us write music per se, but Jon's played things on his MIDI guitar that he feels may have helped indicate some ideas, and certainly some of his sequences that he's running give ideas for the orchestra. So Jon's been instrumental in playing something that we're not going to listen to besides know that that's where Jon wants the orchestration to go, so that's quite intriguing. In the meantime we all pop in bits of piano on tracks now and again, so we kind of muck in a lot more. It's a very good sign in a band when you can do that.

MOT: As you're recording the album, it sounds like you're not making allowances for the orchestra. The arrangements have to work around you. Or is that true?

SH: Well, it's true only to an extent. This is going to work around us. We're sitting in there, and we're talking about tunes, we're working up a tune, and we know that there's four of us, and we know that if we wanted, there's 69 of us (laughs), or another grouping. We know that we can call on an orchestra. We can have a string quartet; we can have the cellos. So it's a lovely feeling to know that we can, if we want, pull in these things, well some of that process-some of that expertise if you like-is what Larry's doing. He's looking for those opportunities to utilize his orchestra, and we commend that, but at the same time we are making our music sometimes with the plan in mind that the orchestra will be performing here, there, you know, we obviously need them here. So they are in our fantasies, if you like, in our minds, fantasy. We're hearing them a little bit; we know that they're going to be there.

MOT: What about synthesizers or other type of keyboard instruments-Hammond organs, I mean, are those pretty much not the sounds you'd like to hear on this album?

SH: We like Hammond organs, electric pianos, grand pianos, Wurlitzers, all that kind of stuff; we love all that-Fender Rhodes. All those instruments that make a sound that is their own. I think once we get the synthesizers, then I'm not advocating it at all. I'm trying to get the band to avoid it, because although if we want some excitement from that world, then I'm not saying don't have it, but I'm just saying don't let's rely on what a keyboard player can achieve quite simply by pressing a key down. If we're not going to rely on that, then so be it and also so be the idea that those sounds aren't doing much for us (laughs). OK, so I could say there are people out there doing great things with synthesizers, yes, but in the wherewithal with us having a keyboard player in the band and having somebody... I can think of many good keyboard players; it's not that I'm knocking keyboard players at all. I'm just saying that we've had that kind of thing around us, and we just want to change that.

Certainly the kind of role of piano is never going to change, and there will be piano on this album. I reckon there'll be organ as well and maybe electric piano, and the varieties of things that that can offer which is really, really great. I don't really think we're looking to have a wall of synthesizers; I hope we're not.

We haven't gone there yet; nobody's ever said, "I want to hear a keyboard," so we're working in a marvelously kind of '60s thinking if you like. It's also the orchestra... look at the Beatles the way they use the orchestra. They had the Mellotron, finally used the Mellotron, but when they wanted orchestra, they used an orchestra mainly because it's actually better than a fake one. But there are great synthesizers out there, and I've worked with people who got great synthesizers and it's hard not to believe that it's not an orchestra, but if we're talking about performance and we're talking about a show that's going to be seen on stage, then obviously... but you know we're not saying goodbye to synthesizers forever, but we're just saying right here and now it's doesn't breathe, work, sound, resound with us, so we're not itching to have a synthesizer player. But we may see a window where [we would use them] but it certainly isn't going to be prevalent.

MOT: I understand that in terms of the current album, but what happens when you go on stage?

SH: Well, our plans for the stage are being discussed at the moment, and they're complicated, and there's a few decisions we haven't made about how one role is going to be achieved, without sending out red lights to everybody who's ever played keyboards who has ever wanted to play with Yes, we're not looking for a keyboard player, like I've said before, we have considered a couple of people inside our own world, not who has ever played with Yes before, but people who are around that we might try out and see if that fits. But we also in a way may decide not to use anybody permanent, because each day we will have used a multitude of musicians, and it really just depends on what decisions we make. We haven't made all of the decisions, but we're doing the tour; we're looking optimistic...

I watched the Moody Blues to see how they did their tour, and I saw their show on KCET [PBS in L.A.]. I watched that with great fascination, and obviously their music's incredibly different from ours, and our music will demand different uses of textures, and we most probably will have some bigger windows for them to come in on. But they did some marvelous-well I call it cadenzas, and it's really not the right word, but sort of like finale, reinterpretation of the whole song. I thought it was a terrific idea, and that really was nice. Funnily enough, I liked the Rolling Stones' orchestral record too, and that was quite surprising; because I like the Stones some, but when I heard the orchestral, I quite liked it. Other groups don't always like the outcome of their symphonic projects. Vis--vis that somebody else is writing their music and going off and playing it. This is totally different from what we're doing now as we have discussed at some length. We're playing our music; it's being arranged by Larry, and we're working along that route.

MOT: From the pieces that I've heard in the studio, I really feel like it's almost like getting back to KEYS TO ASCENSION for some reason. It has kind of that guitar-y type of feel, I guess because KEYS TO ASCENSION was a very guitar-driven album. Would you say that the absence of the keyboards is allowing you to do more in terms of creating the music, and not having a producer there also contributes to that in terms of having his vision put upon you?

SH: Well, I agree with your mention about KEYS, but it also reminds me of THE YES ALBUM, when Tony Kaye was there. Having a keyboard player did allow me to come through a lot, but there were times, like in KEYS when we did record quite often without Rick being there, even in some of the great days that we did-CLOSE TO THE EDGE days. So we've always been used to working, knowing that somebody else is going to play on it, but sometimes it's for clarity that you do that also, and occasionally I don't play and the keyboard player would play, and that would be a thrill for me. But certainly, yes, it allows my songwriting to come through a bit more, because we're not getting other ideas that are totally keyboard-based, although I love them. and in the sound it allows me to do a little texturing more like I do on my solo albums, allows me to create much more of a guitar-ambient sound than just a guitar trying to work with synthesizers.

Maybe that's what I am tired of: the battle between the texture world of synth and guitar. It hasn't always been a happy marriage, and a lot of great records have been made without any keyboards, and a lot of great keyboard records were made without any guitars... obviously the pure guitar, like pure jazz guitar with an acoustic piano is one of the greatest things in the world. But you know the synthesizer alters a lot of characteristics about the way it sounds.

MOT: I guess I can kind of see an arc there from KEYS TO ASCENSION II, more so than the first volume, because that was really almost like Yes back together as we knew them in the '70s. OPEN YOUR EYES wasn't an organic Yes album. THE LADDER was a good album, but it still wasn't quite there, and just from what I hear here, it's almost like back to that Yes level.

SH: Yeah. I think there is. There's definitely a better chemistry when we're not concerned about sharing everything with-like imagine, add two more people to us right now, like we had Billy and Igor, and for all their work that they did for us, which I appreciate, but now it would just be too much. We wouldn't have room for Billy's song, we wouldn't have room for Igor's thing, so in a way for us to grow, we've got to grow closer and work closer together and be much more buoyant and flexible with our approach in sharing our music, when somebody plays something. We've done all this before; I've played Jon and Chris my music for years. I'm totally used to it; I'm totally relaxed. They'll say, "I like that bit, but I don't like that bit." It doesn't hurt at all; I'm really pleased. They told me they like something; that's where we'd spark off on the positive side. Jon might say "I like that; I like that second bit, but could we make it change?" "Yeah." "You want it to change more?" "Yeah." "You want it to change more, even more than that?" "Yeah." It's all exciting, because we're sharing.

Surprisingly, this is quite an advance from KEYS... it's interesting, but there was a period even on this album before I arrived, the guys industriously started writing music, and the same thing happened with KEYS. Because I live in England, obviously I don't want to spend so much time here as they might want me to, so the odd week is drifted in, and I'm proud of them. They get busy writing their music. What happened on KEYS was they'd written quite a lot of that stuff, except "Bring Me To The Power" and "Sign Language" and all that; that was kind of prepared, and I went in and added things to it, chunks of music. I said let's put this riff in here, and when we got to the next song I said I've got this thing to go in here, and then Jon heard it and said I want to sing that, so there's some real synthesis that happened where Jon was singing my guitar lines and all this stuff happened, which is part of what we like to do. So the difference here is that they had the one week without me and were very industrious as well. I've come in and had the same opportunities: "Oh, hang on. I've got something that goes in here." This is the kind of thing we do; we open up the music and say, I might have put something in... I'm very excited that it quite often catapults into some other sections as well.

So the tune certainly grows, and I'm happy because maybe I thought it was a bit too much down here and suddenly how I did this and it's gone over here, so I feel the thing's expanded and so did they, so that kind of writing...

but other times of course, we just say. "What's new," and I'll put on something and we'll play that, and then Jon would say "I think that might go with something I've got." We just start to move and that's the old way, we always written our best music that way. The worst way to do it is send somebody the tape and say we're doing this song, and that's the end, but we can't work with that. A finished song is not actually in any good to Yes because we won't sound like Yes, so no matter how clever any of us are or how much any of us think we are Yes, if you want to get that sort of work going on, you've got to have experience, and you've got to be calm and work together. Sometimes Jon's kind of racey, but at least we get around the curve and on to the next piece of music.

MOT: Except for the simplest of songs, it's not a matter of coming in with a finished piece from beginning to end. It's kind of a refining process.

SH: Well, that's what we'll sit there doing all day is making sure the frameworks that we've got in the ideas that can happen, happen, and I don't want to be in too much of a hurry, because that takes a little bit of time with a tune.

MOT: Looking back on THE LADDER, what do you think the band learned from that experience?

SH: That's a lovely question. It's wonderful because there's just one simple answer, and that is that everything Bruce taught us, you see, Bruce did help us and educate us a lot, not maybe mostly by making the record, but by the experience of having one person to decide... we'd forgotten almost what it was like when just one person had the final say, because we'd made KEYS and OPEN YOUR EYES and of course they'd made TALK and we'd made UNION with a sort of semi-producer concept going on. So suddenly Bruce was there and he said he likes things to run easy, "OK, so I want everybody there at one o'clock. Is that alright with you." He'd look at you like this. "Is that all right with you?" You got the picture straight away; he was punctual, and his bands were punctual too.

So I think the whole thing started with tremendous respect. We had a respect for him; he had a respect for us. When somebody good is around a band like that, the band shapes up a lot. A lot of crap and bullshit has to go out the window, because, hang on, we're working at this level now, and a lot of things have to go by the by, and you have to leave some subjects. You realize that in a recording studio, you're in there to work on that recording. You don't have meetings; you don't take calls. You don't deviate from your topic of conversation sufficiently to lose the plot. You work on music all the time. Yeah, we'd break, we have lunch... what Bruce brought us into, was decision-making, process changing. He'd hear what everybody thought-"Do you like that Steve? What do you think, Jon? Chris? Alan? OK. Billy, Igor... OK, we're doing it Chris' way." He'd agree with one person-and maybe he wouldn't say we'd do it Chris' way, he'd say, "No, I agree with Chris, I think that's the one we're doing." So, he would make decisions, He might say, "You're all wrong, you're doing it this way," as well, but he was great.

He was really practical... rehearsals; nobody had given us that time, when they would come to rehearsals for two weeks for about three or four hours a day and sit there and talk about the songs. This was tremendous work he did on us. So what happened on the record wasn't just based on us walking into the studio and saying "Hello, Bruce," then start recording. It was brilliantly planned, masterminded, all under control and then the worst thing in the world happens is that Bruce passes away. We would have liked Bruce to be there on the mix. That's how I feel; everyone in the band would have preferred Bruce to be there, because he did steer us. "Nine Voices" is one of the tracks he mixed, so take a listen to that, and if you listen to that and then listen to the album, then you know what he wanted, but that was very subtle. So we learned from Bruce that you got to get your act together; you get ready, you rehearse.

MOT: Are you applying that today?

SH: The way we're applying that today is that we certainly remember what his sense of organization planning did for us then. But having done KEYS TO ASCENSION, we kind of know that we're all right doing it this way as well, because it's a different style of production, not only in the sense of the word audio, but also in the sense of the way we're able to not hold somebody up so long as we were holding Bruce up. We had him for quite a few months, and it was just great. When Bruce died, we actually said there isn't another Bruce. Suddenly we lost a friend and also we lost a potential future. We thought it was the beginning of a relationship with Bruce, we hoped it was. So in fact for us it was doubly disappointing, and doubly sad. But I guess we've regrouped and rethought our plan. In a way, we've hedged a lot of bets, but it seems to work for us, because we are more like gypsy nomad musicians. I suppose we don't fit very well into a pure totally corporate way of working. Left Bank Management are very gracious, because we are somewhat our own masters of our own destiny, but they've been patient with us and let us have this much freedom we're now finding so useful.

MOT: Management is basically letting you create your art the way you see it and not dictating any terms.

SH: Right. They want the best record we can possibly make.

MOT: It's nice to hear that, in that a rock-n-roll management is nurturing, really...

SH: Instead of a guy thinking, "Wow, I manage Yes. Now it's time to go out and try to get $3 million for this project, and we'll go out and talk to him and buy this guy lunch." That's such a load of shit; I'm so sick of that.

MOT: Were there any producers that you considered prior to deciding to do it yourself?

SH: In a way, I'm slightly underestimating somebody's presence by saying we're doing it ourselves, because we're not engineering this record ourselves, and engineering is a very vital and incredibly important part of the process, so we're working with Tim Weidman, and Tim was brought in because we wanted a top engineer who'd been working in London, working in England a lot, who could bring to us some awareness of the fact that we come from there, you know what I mean? So, rather than work with somebody who's really familiar or at home here if you like. Tim and I align quite well, because we're both from over there. So Tim Weidman's done years and years of recording, and he is an extremely good engineer, he's had a lot of experience through records with Seal and many other bands with Trevor Horn, and maybe ought to make that CD sound even better than that, and he is. He's worked with a lot of important people, so he's had that. He's got his own style, which the guys have kind of gotten used to now I guess, and he seems to be the right guy for us. He's holding the fort, and he has something important to bring to the table, which is learning about understanding us and understanding about what we want, but at the same time, bringing his expertise from all the CDs he's made.

MOT: Many fans are interested as to why Igor is not involved in the project.

SH: I think it's like I was saying about the opportunity for us to write the way we were writing on KEYS, is so appealing to us-that we can exchange music in so many different ways. We can't do that with people who haven't been with us on that journey, haven't been with us on the inroads and outroads... there's almost like a behavior that needs to exist, and I think you can ask a producer to produce the behavior that you want to from people. I'm not talking about anything noticeable about behavior, I'm just talking about interaction in music, the way you write, the way you work, the things that aren't said, the things you don't have to discuss, the key changes that are just done without, "Are we going to a B flat?" There's a grace and an ease of work.

I guess that I was thinking about in general, Yes members ... how many long-time members can you have together, is the question I was trying to ask myself. So I was looking at that because Igor and Billy were both currently quite short-term members. I don't mean, like Patrick, they weren't able to bring something to the party, but unfortunately making that last was more of an obstacle then the excitement of when it happens. It happened; it worked. It all worked well; we did it, and then things seemed to go in a different direction, like when we did Masterworks and we decided that Billy wasn't maybe in the band for that reason. We couldn't go back with Billy and play. We didn't think it was necessary to have Billy to play that music. It was difficult enough for us to play it, and bringing somebody else in was going to be a colossal idea. Not that he couldn't have helped, but in the overall way, we saw the time was up for that member. We were going to move onto another era; and once we did that, the next stage is really Igor.

It wasn't that he did anything particularly wrong; it was just that the relationship evolved in a way that meant that we moved on maybe quicker than he did, and maybe that's it. Maybe that's what we've got. Jon, Chris, and I particularly, and Alan, were able to keep seeing a new way, and if I don't know whether we asked our members to say we could see that. We certainly don't, but I think that's what we've always brought to it, is a strength of belief... I don't think it works so well when you've got people who... this is a team. It works well like this, so at the moment, you know, we're going to get 69 people instead (laughs). That's a great answer, isn't it? "Why haven't you got Igor in?" "We decided to get 69 people instead!" That's basically what we're doing.

MOT: It was mutual though too, wasn't it? I mean, maybe he thought it was time to move on as well.

SH: Look, in an ideal world he didn't want to leave the band. In an ideal world we didn't want him to leave. We would have liked him to have fulfilled the fantasy that we wanted. But what he couldn't see I suppose was the same thing other members haven't been able to see, even Bill when he left. He couldn't see what Yes could do around the corner, or how this could transpire. Sadly, Bill's one of the very few people who actually just left. I mean, Rick did leave, but I mean, leaving a band is-how can I put it-when you go in and you're about to be fired, and you go in and you just realize 10 seconds before the guy opens his mouth and says, "I'm going to fire you," you say, "I've decided to leave." The guy is thrilled to bits; I mean you made it so easy for him. He doesn't have to fire you. That's the same life in a band, as well. You can leave, but that certainly wasn't the case with Bill, because Bill adamantly wanted to leave, and we adamantly didn't want him to leave.

MOT: One thing I was interested in is about performing the songs-not the new material; I'm talking about performing any old material. Were you saying that it's conceivable the orchestra would handle those keyboard parts as well for any old songs that you perform?

SH: Well, that's fundamentally what we're going to do. We're not asking him necessarily to arrange a new arrangement for these tunes; we're asking him to create a possibility [where] the keyboard parts could be played by the orchestra. That's the function that we see them doing; we think this is an interesting idea-interpretation. Some of it, in itself, attempted to be what an orchestral was, so would it be that unfamiliar? I don't know. But it would be interesting to have a live quality of performance brought to it.

MOT: You would have a different orchestra in every town?

SH: Yeah.

MOT: Could there conceivably be performances without the orchestra for some reason-a technical reason or something like that?

SH: No. Well, if you pull the plug out, Mike, you won't hear them.

MOT: (Laughs) We're looking forward to the new album. So, let's move on to NATURAL TIMBRE... you're [pronouncing it] "tamber"?

SH: "Timber", "tambre", "tamber"... "tambre" is more French or European, but "timber" is totally acceptable under any other circumstances.

MOT: Just as I asked you why an orchestral album for Yes-why an acoustic album?

SH: Well, I would just answer: at last. It is a breakthrough I've been waiting to make. It's funny how I've been knowing that when I was going to be able to do an acoustic album, that it would have to feature solos. Now, to get those solos-to get a lot of them, is really tough, because you have to have some years of writing... it's not so much that they're difficult to write, it's more they're difficult to perfect-to bring them to performance, so to take a tune out of your mind, yeah, write it, yeah, that's one thing, but then actually play it and learn to play it with right change, with the right skills, on your own, that to me is a slow process.

Fast process is put some programmed drums down, put a bass on, put a few guitars on-I got a song finished in a day. But a guitar solo will take me years... not years (laughs), but over years I will go back to this piece and think I'm cookin'. Anyway, eventually Eagle, after

PORTRAITS OF BOB DYLAN, which they liked it very much, asked me if I'd do an acoustic album, so I said, "Well, you just asked me the question... yes." So I went off and looked at a few tracks I had, and thought, oh yeah, well I've got to play this and play this, so I started thinking about what kind of album I could do, and they came back to me and said how about doing some Yes tracks on it. So we went back and forwards on this idea, and I let it sit for a while without really saying-I knew I would be happy to do "To Be Over" and I couldn't imagine what else I could do with it, because it was the only one I really wanted to do. It was like, well, I really do want to do that, but it's just one, so they said a couple would be nice, think about it, so I said, well, I'll see what I can do. But that's another thing-this album, it's got to feel like my record and not a retrospective record, so that's why we present all my new music first, and Yes follow it as a sort of an extra, because the album kind of finishes with "Solo Winds", and that's the way the album finishes...

So, I went through this time of looking at what I had, and then I thought about what I could write, and I thought about when I could do things, and then the first slot came up where I thought, oh yeah, I could really just say I'm on the album now, so I got in my studio, and I just thought, if I don't do some solos right now this album is not real. I've got to feel this album; is going to be really exciting, so I recorded about three solos that week, and it started me off on such a good footing that I thought, ok, well now I can lean back and think about what else I can do. And I'm not going to play solo the whole time. Sixty minutes of solo guitar-that's a real challenge, and I admire everybody who does that successfully, but it wasn't for me this time. I sensed, I wanted to group and do some textures and play some dobro-acoustic-wow, what a window to open.

And then I went through the "Oh dear, this is going to be really difficult," because with an electric guitar you can do so much to it afterwards, you could put treatment, create other dimensions, kind of do that. So once I got around to thinking that I was just laying all my electrics to have a rest for a while, and all my acoustics, it was quite fun, you know I was just in this world, one world. I wasn't playing electric guitar, and that followed through that period, and I did a tour, came back with some more work, did another tour. It was kind of done between last year's work, and by finishing it at the end of January, was quite a stroke; because-I did this with I think PORTRAITS OF BOB DYLAN-it allows me to record out in the same year that I finished it, which I really like, because I love the feeling of this is now. This is what I just did; I was just playing this a few months ago. It's a nice feeling. I guess the quite carefully planned balance of solo tracks and groups of instruments, a duet, three pieces here and there, I really found the album just a pleasure, you know; it was a pleasure to my ears, because I was wrapped up in this wooden sound.

MOT: Of the new material, how much of it was conceived especially for the album?

SH: All of it really (laughs). Remember what I said to start with, that this album was growing as I was going along, so it was a bit like my first album, like BEGINNINGS. By the time I got to this album... I mean there were tracks that could have been half electric and half acoustic, then I trimmed out all the electrics and just said, "OK, how does this work now?" And it worked, and then I went back and added more acoustic instruments, so some tracks were already acoustic so much that I just had to think about them more because I had electric things on them; just think, "Oh, we'll take the bass off of that," and suddenly that is a good idea. So I had tracks coming in as contenders. I had solos I was finishing up writing, and then attempting to record, and then I suddenly thought, God, if I did that track "Distant Seas" I would have to do that with drums, and I thought, "They're acoustic! So what!" So then suddenly Dylan was on the album, and that really pleased me, because he plays on four tracks, and I thought, well, now the album's grown, it feels like a huge thing to me, because it's got all these different facets of my acoustic work... and still "Provence" is another track that's had a lot of work.

This comes from music also that I've been making over the last ten years. "Golden Years" is a very old piece that I wrote years and years ago, and I'm always doing that, things gone forward; a piece like "Intersection Blues" was more spontaneous but some of these pieces I recorded two or three times before... "In The Course Of The Day", part of that tune I only wrote three years ago, when I was in Livitz for six weeks I wrote that tune there. And then the other half of the tune I wrote in the '80s when I met Roger Dean's friend Ian Miller, and I bought some pictures from him, I liked his art, and one of them was called "Hollywood Gothic", and for a while I used to call that piece "Hollywood Gothic", and then "In The Course Of The Day" came along, and I thought no, the right other half of the tune. I like writing music. I love having the freedom to do it myself and create my own sense of spontaneity here and there. I love doing that; that's what I like to do.

I mean even Vivaldi, there were improvisational sections in classical music as well. Originally in the Middle Ages, in the Renaissance period, there were areas for the musician to find his own idea in a concerto for a violin. People forget that, and I think that's why I like that in my writing too. I like to invent all the time; I don't like once you've committed it, you're going to play it like that, but prior to that total commitment, that release of a recording can change a lot. I can decide to take half of it out.

MOT: Yeah, maybe along those lines "Winter" seemed a lot more opened up than the version on your live solo album.

SH: Right. Yeah, that recording really pleased me to use it, because I thought having two arrangements of old music in the album was good. It showed some interest that I have in music very much beyond my own lifetime. "Winter" is a lovely tune, and what happened was this album allowed me to consider the mandolin much more, like I did the steel guitar in the '70s on my solo albums, QUANTUM GUITAR in particular, was very heavy on steel. This time I definitely wanted to play dobro; because I dearly love the dobro, and Hawaiian steel guitars. Also playing a little Spanish guitar, which I don't always get a chance to do, and acoustic bass-golden opportunities.

MOT: On first impression it seems like it's very much a steel string album more so than classical guitar.

SH: [Looking at the track list] Well, actually the Spanish guitar is featured all the way through the first track, most of that is Spanish guitar [sings part of the tune]. "Steel Pictures", the solo's a steel guitar; "Family Tree", maybe that's more steel-strung, yeah. "J's Theme", that has a Spanish guitar solo, number five... steel-strung, steel-strung, yeah, dobro's a steel-strung. "Galliard" is on the very early Spanish guitar that I played, from 1815 maybe, called a Ponoma. "Up Above [Somewhere]", steel, "Curls and Swirls", steel... "Pyramidology"-Spanish guitar solo, so that's three Spanish guitar solos, besides it being all over the first track with drums, and then "Solo Winds", once again another Spanish guitar solo-a long-winded sort of track. There, I punned my own title!

"Solo Winds" is a very long-winded sort of track... I love space. I know that by the time you get to the end of this album, I feel that you need space, and that's why "Solo Winds" is quite an airy sort of a track, and there's some other ponderous moments, and then I go onto the Yes tracks, which I hoped very much that the Yes audience will like. Quite a curious thing, I wasn't determined to put them on the same record at first; I wondered whether it shouldn't be a companion recording, and then they asked me would I do a whole CD of it. I said no, let's just think about this, and set me off there.

MOT: I think the fans will really like those tracks. In fact, I was almost half-expecting a real Sitar on "To Be Over" (laughs).

SH: Oh yeah, believe me, I got out my Sitar. I was almost determined to go down and buy a new one, because my one was really in a state, rusty and things like this, and I did wonder about the Sitar, yeah. [Sings part of "To Be Over"]

MOT: Well, because the Coral Electric Sitar figured so much in the original.

SH: Yeah, but putting things to things was really good for my mind. What I did on "Your Move" was really the height of it, because I told you I got "To Be Over", that was firmly in my mind, "I can do that on there." And then I was kicking around the other songs, and I kept going all over other place and I kept thinking, no, I don't know. I suddenly looked at "Your Move", and I thought, what if I did this? If Jon was a guitar and Chris was a mandolin, and I was a mandola-I know those parts. It wasn't easy doing Jon's part, because of course I had never sung it, bar casually, and so I listened to each verse and learned each verse one at a time and then played them on the recording, because they're very intricate, and Jon may not even think about it, but obviously his innuendos on the notes, I try to mimic them very very closely, and it's not 100%, but it's as much as I can get, because I wanted to establish that, and then put Chris and I around. I think I'm close to the middle with Jon, and Chris is on one side, on the mandolin, so it was also logical. I'm a very logical person, I'd like to think, and sometimes I exercise that in my music, and this was so logical to do. I could play the Portuguese, I could have fun with the bass drum, the bass. It was all great fun; the whole album was nothing but a new kind of excitement, really.

MOT: Yeah, on "Your Move", your replicating the vocal melodies was very precise.

SH: Well, right, it was my idea that Andrew Jackman would carry on his recorder part and play "Give Peace A Chance", and it works so nicely, and I thought I was really pleased. The thrill for me was that I could see how one's mind after "Your Move", you think you're going into "I've Seen All Good People", and of course on acoustic guitar this didn't do it for me at all, so I had this weird idea that I was going to do "Disillusion" where I could do that as a tune; so I did the same treatment really, I took Chris and Jon's voice and put them on different styles of Hawaiian guitars, and I had fun doing some leads on this, because actually every night I'd play it, I always thought I could do more on that, "Loneliness" [sings part of the song]. I could do a break on that, solo, and of course I did that on there.

MOT: After playing these particular songs after all of these years you'd have to play the melodies...

SH: Well, yeah, I've played melodies that were familiar, but not mine, but the other thing was that "To Be Over" was so unplayed and unsung. It was like this song has just been forgotten about, or by Yes themselves, we had not played that song.

MOT: The recorders on "Your Move" are just exquisite. I heard that and went, wow!

SH: Andrew did a great job, and he did a lovely thing on "To Be Over"; I was doing all the playing on this record, and very few other people came in and did things, and when they did it, it was usually based around what I did. Well, Andrew came in and said to me had I noticed this tune in "To Be Over", and he went out there and played this tune, and I said, ah, I don't know. I hear a whole lot of stuff near the end, when the tubular bells come in, and I wanted him to simulate the tubular bells, and we did that on glockenspiel. So obviously things have to get scoured into the regional sound that we wanted, and then when he played the piano, just when after middle 8-"After all... " [hums of last vocal verse of the song], well it starts off there is this beautiful piano that goes [sings a part over the closing section of the song]. It's not playing any of the familiar tunes that have come in the song, which I do when I play [sings his into to the song], but this was really a nice find, and he brought it to the table, it's nice.

MOT: He did a great job on those recorders.

SH: And, Anna Palm is the violinist; she's on about three tracks, and she does a duet with me on "In The Course Of The Day", and I like the texture. I liked the sound that she makes; I like to bring in some other voices, so to speak.

MOT: So, there's only one cover song, or are there more than one?

SH: Well, you wouldn't know, but "Galliard" is actually called "The Little Galliard" is actually my arrangement of a John Dowling piece. I've been playing it on some of my solo shows over the years, occasionally. So, I've arranged it, and I play it on this Ponomo guitar, which is in my book. So playing it on that guitar, although it's not as early as a lute would have been in the 17th Century, the album starts to lean a bit towards being about my collection, because I was playing a lot of guitars. I think I played 22 guitars on the album, which are listed. The sleeve is going to be really good. On QUANTUM GUITAR, we did a sort of graph that went tracks and guitars. So we did a really totally mindblowing approach, like eighteen tracks with twenty-two guitars all on one piece of paper about this big, but you could really see it quite well. This has been an in-house production by Eagle Records, and it's been a lot of fun because I could really exercise my ideas.

MOT: You touched on one of my questions about some of the rarer instruments that you may have used.

SH: Well, the sleeve is quite explanatory, but in the most part these twenty-two pieces cover instruments that aren't guitars; like for instance I play Autoharp here and there on the album and also Koto on the opening track and of course acoustic bass on a few tracks with drums, but the others, yeah comes from my prized acoustic guitars, but it's a refinement, it's not a big broad statement. I'm not trying to make a statement about the guitars in a way, only a small statement... what I'm saying is that I didn't use every Martin I've got or every Gibson I've got. I didn't go for the "everything" sort of album. No, I just used the things I needed, the things I like and I'm more familiar were the guitars I use. A few guitars came in that have never been recorded; I've never played Gibson acoustics before, and yet two of those tracks are on Gibson acoustics. Both picking tunes aren't on Martins; I mean it's a strange thing that happened, it wasn't intentional.

I use the Martins extensively during the album for other picking parts, but picking solos I really found I wanted to change the sound. I wanted to play them on Gibson-not that I wanted to play them on Gibsons [particularly], but my Gibsons were just sounding good, so I played on the Country-Western and my Steve Howe Custom, so I've quite pleased about that. I like using my guitars in different ways. Both of my 0018-SH's are on there, all over the album, and then what I did with my very, very rare Sunburst model is that it's a Nashville guitar now-it's always tuned for Nashville. Guys love it here, putting it on the album too, so it's tuned just for the six-string Nashville tuning.

MOT: What is Nashville tuning?

SH: If you took a twelve-string and took all the regular set of strings off of it, imagine what you'd have left-looks like a funny set. You've got an E-string, a B-string, and you've got like a high string, and then you've got another high string, which is an E-string tuned to D, and then you've got a B-string tuned down to A, so you haven't got any low notes basically, and you've got one very high one in the middle, so your chording versions sound totally different.

MOT: So, the notes on the strings are exactly the same, it's just that the gauge of the strings are different. Any other thoughts on NATURAL TIMBRE?

SH: Well, I think, well I've done records before and thought they were personal, and I suppose PORTRAITS OF BOB DYLAN in a way was a personal statement, but it wasn't my music, and I guess doing my music, as I do so much on this album-besides the Yes tracks-doing my music made this a more personal album than usual. It fulfilled certain fantasies that were all about, little did I realize, acoustic guitar music much more, and in particular as an example the opportunities I gave myself in "Golden Years". So yeah, it's pretty personal. I hope it has more of a romantic feel to it in a way; there are some quite romantic qualities about the music in my mind.

MOT: Are you thinking about selling it to other markets? Like the whole acoustic market?

SH: I think that's a very foreseeable situation. I mean, obviously, as a writer or as a musician, I like to be enjoyed. There is a logical conclusion about reaching the point, because when I would do the album, I wondered if I would do more albums, but actually I think I will. I think acoustic is a very important part of my curriculum.

MOT: Actually, I saw it as more as one of a series because you've always talked about doing other different types of albums, like the jazz album...

SH: Well, I'm heading into doing this R&B blues album next; I think that's what I think I want to do at the moment, but something else might come along. I'm pretty keen on some of the material I've got at the moment, and I might like to write some more. Minidiscs have kind of helped the writing process a lot, because you can jump about so much and carry ideas that you need actually. I mean, I've got a brain, and it's a pretty good brain, but there's no way I could remember 120 pieces of music, little snippets of ideas, but I put 120 on a Minidisc. I'm actually getting to know them, because they're all together now, but they're ideas drawn from other idea tapes, just put onto one Minidisc, and they're all just like a riff, a chord progression, maybe a song or quite a few songs, but they're not formulated. They're not structured; they're written, really, they're just that they're ideas. It's great to have that and be able to write between all these different pieces of music, because they're all on the same mini. You can reorder them, and suddenly you have this going into that... amazing.

MOT: Let's talk a little about the Oliver Wakeman project. How did you come to help Oliver on the album?

SH: Yeah, over the years, Oliver's been living in Devon, and I've been in Devon a lot-especially in the last ten years, writing and recording at my studio, so I run into Oliver, and then Oliver is the eldest son of Rick, and we've always gotten along really good. So eventually he came to me and told me about some of these projects, and he came to me with what he wanted to do, which is this record, THE THREE AGES OF MAGIK. I was impressed with his organization and his presentation, it was pretty astounding, so we kind of start talking about what I thought about the ideas and would I play on it, and I kind of said I'd like to help pick through it and work through some of the stuff, look at it all... anyway I became the executive producer, which means I kind of oversaw things. I advised him; I suggested things. I occasionally edited things and said to him, maybe you've got something else. Sometimes he'd just come back with a whole new tune and say what about this tune instead? And I said, yeah, that's better. (laughs)

So, in a way, I was just sifting with him, and not writing with him exactly, just sifting and increasing the continuity that I thought was there. Then I started playing on it, and then I played on the whole record (laughs).

It's just one of those things that happen. Sometimes small beginnings are good; nobody's got any big ideas. They're just thinking about, can you help, and then suddenly the ideas come. Oliver just hoped that I would contribute as much as I wanted to. Oliver and I started to work well together; you know if something is going well if we're both interacting, and then when he heard some guitar stuff, he said oh, that's great. I really went pretty much to town just with one guitar usually. We'll do a rhythm guitar and then a lead guitar or just a Spanish guitar. There are quite a variety of different guitar styles on it, between some acoustic-but what happens is, what I like about it, is I'm not the ever-present guy trying to put his nose in the music. I come thundering in now and again and get quite busy, and then I leave him for a while, and he's rocking along just great himself, and we don't need a guitarist. And other things come along where I did do some background stuff. I did do some good rhythm work, and those ideas kind of had a little hook in them, a little bit of a part in them, so it kind of comes through, so I'm not always busy in the front, but there are some good breaks on it, and there's a duet we did together that I tell you, the Spanish guitar duet could change the world.

MOT: Spanish guitar and what, piano?

SH: Yeah, it's a very good piece. So we've got some very strong pieces on there, and I think it's going to be well received. I mean, one's got to say he's Rick's son. He's been influenced by Rick certainly, but he's become his own musician, he has much of the ability to lighten up the mood like Rick does. It kind of brings a smile to your face sometimes; it kind of lighten things up nicely, and lots of color and great synthesizers. I mean, there's a guy who's doing good synthesizers, and it's nice that he's all encapsulated. He's got real drums and bass on it; it's not a record with anything fake on it. He's got his synths; he's got loads of organ on it. He's really shared the spotlight with a guy who's played pipes, a violinist-I thought this album has grown beyond what I had imagined, at first I thought it was going to be like him and me, and I would assist, but he had his ideas. Once we got past real bass and drums, he wanted to have pipes, "Got a guy to come in and play the pipes, I hear this pipe coming through." So the music is not just about a keyboard player's backroom fantasy, nothing like that. It's a real concept piece.

MOT: Pipes?

SH: Irish pipes, like bagpipes. They sound like... the guy's just come from Hell [sings booming notes]-all these strange notes. It's a wonderful, eerie sound. Irish, very expressive and mournful. They're one of the most expressive instruments I've ever heard.

MOT: That sounds pretty fascinating.

SH: It is, it's fascinating. So I'm up on the Oliver thing. He's got his musical style; to me, it doesn't interfere with my work with my sons. Their careers are totally top priority with me; my work with Oliver is on a friendly and a professional basis. It's a sincere, knocking on neighbor's doors, it's a bit like that. It's a nice friendship. As you know I work with Virgil a lot closely. I endorse what he does and encourage him on his drumming, his keyboard playing, his remixing, his whatever, but I don't have to do anything. I mean, it's him doing it, it's not me; he's very busy and the same with Dylan with his drum career that he's taken on full-blown, so he's very busy too, he's working with Gabriele, a very successful singer in Europe, so he's got his own CD coming out called THE WAY I HEAR IT. So they're really my priorities, but Oliver is like a friend who I play with now.

It's really quite fun; we make it easy for each other. We did that recording in such a casual sort of way, it was great. I did half of the guitars at my place, and then when he was at the studio I went down with electric guitars and handed out a whole lot of stuff in one day and really tackled some pieces I was scared of. There is a piece called "Hypersail", so I was like. "You really want me to play on this [incredulously]-right, ok. You really, really got to get me on this. You sure?'" (laughs) it wasn't quite like that; it was that it was a challenging opportunity.

MOT: What is it like working with Oliver, in relation to how you work with Rick Wakeman?

SH: The musical style aside, the way we've worked is parallel with the way people work today, and fortunately for our time, Rick and I were capable of working together when technology wasn't what it is today, it was so much more hands-on and in real time. Now, of course, I can record in my studio with a slave, Oliver can hear my work. We can work when it suits us, when it fits. You don't have to stop our lives to work on somebody's record nowadays. You can fit it in around other things if you want to. And so I saw it as something that was quite nice to have on the edge, that I could just over a period of time update now and again, when I had an afternoon and I thought, oh, I'll stick that guitar in. What, it would take me three hours to put a guitar on. I wasn't building a track; that takes me all day, so in fact playing guitar is something I love... if I stopped recording Yes or my solo albums, I could most probably play on a thousand people's records in a year, because I could play around-not that I want to do that or those numbers are sort of like what I think about ever, I don't-but I certainly know that it's fun working with different people, and technology does allow that even to the extent of through Pro Tools in different countries. You can connect and record stuff that you can hear straight back and send mixes.

But I'm not a technical operator. I enjoy technology basically because I don't operate it; I think of the ideas that it can do, once I understand a little of what it might be able to do, so I'm just a guy that keeps going, "Well, I'd like to do this, can you do this?" (Laughs) But to have to do it all would confuse me, so much like Rick and my work back then, we didn't know that it was going to be this easy to send stuff around. Even in the '80s, you had to have a 24-track multi-track slave synchronized with something hopeless, like an SRT or some type of machine. I would have never believed it, but it's remarkable. Technology has allowed Oliver and I to work-sometimes we'd just sit around and talk like this for a couple of hours. He'd go away, and then like two weeks later he called and say, hey, "He've got a couple of tracks done; I'll send you a cassette." He sends me the cassette, eventually Minidisc when he got one, and then that was the way it would kind of go. We'd exchange the things, and he'd see I was making a bit of progress, and it was a process of just seeing the album wing through almost on the side of the other things I was doing. I'm pretty good at doing that.

MOT: It was nice being just a guitar player though you gave advice... a mentor.

SH: In essence, I was fundamentally the guitar player, but I did bring up certain points and discuss the use of things and encouraged him as much as I could to keep going on dreaming up sounds and not using many sounds that have been heard before or used too much before. It's good fun.

MOT: Your own sons are carrying on the Howe musical legacy, although neither of them play guitar, so they're not carrying that part of it forward.

SH: Virgil's talented, he knows a few things on the guitar, I think that gradually he's thinking he might learn a bit more guitar. Dylan's has a guitar also, but, yes, in the forefront, they're not working that skill much, no. Guitar is quite a complex instrument I must say, and I think I was lucky at the time when I started to play; I was able to focus on I, I was able to kind of cut myself off in certain ways to learn the guitar, and also there's a lot that hadn't been played, but there again, to my ears there was a lot that was never going to be played again. Obviously there were other people as good as Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt, but those kind of caliber of guitarists went through the '60s, and fell into decline more in the '70s, '80s, and '90s-less of the truly great greats. You just couldn't have more; it was an era called, I think of it as, Bebop guitar, when jazz came through and a whole world of musicians... Kenny Burrell is one of the great jazz guitarists of today who's carrying on all the traditions of the great guitar heroes that I admired. As a guy told me who works in a guitar shop, sometimes he has to remind some of the young guitarists that there were guitarists around before, like, Jimmy Page, or someone.

MOT: (Laughs) Actually, it's almost appropriate that neither of them are playing guitar.

SH: But it allows us to be very uncompetitive, not that I would be competitive, but the struggle for...

MOT: Well, you're a lot to live up to, Steve. (Laughs) As far as a guitar player goes, I mean hopefully they'll live up to you in a musical sense, only time will tell that.

SH: Well, the marvelous thing is it's great for me to know that my sons are aware that I'm a gifted guitarist, but that doesn't put them under the pressure to be that. I think they quite enjoy that; that's why they're being their own people. I think surprisingly as much as I am not only musical on the guitar, but also I musically interact with people-I don't just sit in a group and play a guitar, I've always interacted-and my sons do the same thing, so they take on some of my interactiveness as well. Besides, I believe I've got a very equal talent, but they take on some of the ability to talk, discuss, and try to be a useful musician if you like, but also a creative musicians, somebody who's adding something useful.

We've seen Dylan on stage and just known that he's doing that. Some people might not notice it as much as we do, but we know what he's doing is much like Bill Bruford did; elevate the music to a greater standard of excellence. Somehow this drumming is fresh and alive; it's remarkable how he comes on, and he comes on like this is really important. This is shit-hot, this is right. We are on, and he's very much an on performer, like Virgil-you would not believe what's he like on the drums. He drives them like mad-thunders on the drums.

MOT: I've heard him. [That day I witnessed Virgil jamming on Alan's kit, both alone and with Steve.]

SH: Well, you've heard that, but hear him in his band when he's doing the kind of music that they play, so to speak, is definitely a wonderful experience.

MOT: What about Georgia and Stephanie?

SH: Well at this moment, Georgia's an incredibly successful student who's going into the university soon, when she's finished her year of school, I think it might be October, and she's quite talented musically, actually. She reads music; she's one of the only Howes to do this to the degree that you can sit and play a piano by looking at it. She wondered if she might have missed the opportunity to be improvisational... I think she can do that, but she also doesn't want to take music on as a career. She's got so many other opportunities; she's not thinking about at all, even though she plays a very nice piano.

Now Stephanie, who's fourteen, really hasn't made up her mind about these sort of things, and she's busy working on school, working very hard getting great results, and she sings beautifully. She can sing lovely, but she does lots of other things as well, so this time in her life, they're much freer than I was in a way. There was less going on for me; even though I was in London, it was boring, and the guitar was almost like an addiction I got, because there was so little else really going on. I didn't make a lot of things happen. Sure I could have been more social; I was reasonably social, but I worked by entertaining people, and learning the guitar was, I suppose, something I wanted to do well.

MOT: I wanted to wrap up with KEYSTUDIO.

SH: This idea comes along that this music that we did together in San Luis Obispo got

kind of lumbered down with all the live material, so discussions went between Castle Communications and members of the band, and it was decided that maybe we could put the music into its own context, not treat it as any part of a live experience-live photos, live stuff... it just became visible that we'd missed the plot, that that material was in fact was a studio album. That's how it's being presented now, and I suppose the idea is if you like programming your CD, you can do this at home, but we've done it for you by rearranging the tracks-adding a couple of bonus tracks to the project, and putting the CD in a context of easy listening, where you can go through the KEYS TO ASCENSION period, but without the mention of live music.

MOT: You restored the keyboard and production for "Children of Light", that's actually almost legendary amongst Yes fans, because Rick's spoken out at length to me in an interview before KEYS II came out, and I was excited to hear that.

SH: Good. The other unheard thing is of course "Second Time Around", which is where we were experimenting with...

MOT: "Second Time Around", is that an unreleased song? ["Sign Language" ultimately did not make the album as was no room for it.]

SH: It's not quite that exciting. Jon was singing kind of over "Sign Language", if you like, so he had an idea about the song. At the time, it created a bit of a tension... it became clear that now it isn't a tension, it's seen as a piece of alternative work if you like, and we didn't put it out at the time because we didn't think it worked, but now it works in the context of being something that haven't even been really discussed by anybody, which is interesting, so it's more of a surprise that we just tagged into... we were having this much fun really; we didn't always know it, but we were kicking stuff around and trying out everybody's ideas. And of course we wrote the big one "Mind Drive".

MOT: And we all want to see that on some future tour. (laughs)

SH: I'm going to start working on it one day... one day very soon (laughs).

MOT: As far as that keyboard part goes, are you glad to see it back-the intro to "Children of Light"?

SH: Yeah, I was pretty torn when the reasons that intro wasn't included, wasn't wholly musical before. There was a little bit of a whoops, and then somebody, just by chance, somebody sent the version all the way back to the beginning, and suddenly somebody went, oh, that's ok, and everybody went, "I guess that is OK." But then when I had listened to the album sometime later, I detected a horrendous bash when that track comes in. It doesn't feel terribly natural, because we were used to it actually after this kind of orchestral maneuver if you like, so there you get the maneuver, you kind of know you're set up for something and then comes in very nicely as it didn't the edit. So, that's an improvement.

MOT: Maybe bringing all the tracks together with the sequencing it will be much stronger.

SH: It is-it is. I put them together and they work like that, they had to put them in perspective. Though it's not like a pop hit record, it can't be planned every time but your running order has a logical thing it's got to do, and it's got to do that, and you don't know how until you finish the track and you're going, oh, that one fits here. Like the curve of some sort of event, you've got to leave them. How do you want to leave these people. Do you want to leave a [makes a loud noise], or do want to leave a [hums quietly].

I love that Monty Python thing, I use it so often, but on one program they did ended where I think a guy was telling a story, how something had to end, and they're in a shop. And the guy turns to another guy and says, "What do you mean, an ending like this?" And everything goes black! You just stand there for a second, you just see a black screen. And the screen comes back ultimately-"No. No." "Well what did you mean? A slow fade like this?" with people fading away in this distance. This is just great how you can talk about it, this is how it ends. Not only a film, a television program, but a piece of music as well. So all this is fascinating.

MOT: [KEYSTUDIO], probably the last great Yes album, has some great Yes songs on it. It's almost as if Yes is now taking up from there, because of the sounds of the songs and the way you're working together.

SH: It's more consistent with the style of music we're doing now. We're working in that mixture of chemistry that created that. But also it's the same people who did GOING FOR THE ONE, TORMATO, as well as all the others. So in a way we have been the mainstays of Yes. Especially when you consider how much part sometimes keyboard players haven't played. Rick played vital parts in big songs like "Parallels", and things like that, and other stuff we'd been working on.

MOT: So, some exciting times coming for Yes.

SH: Hopefully. Yeah, hopefully for all inventive musicians, so who knows.

Notes From the Edge #250

The entire contents of this interview are

Copyright © 2002, Mike Tiano

ALL RIGHTS RESERVEDSpecial thanks to Jen Gaudette

© 2002 Notes from the Edge

webmaster@nfte.org