MIKE TIANO: Iíd like to start with the book. I was looking over what you

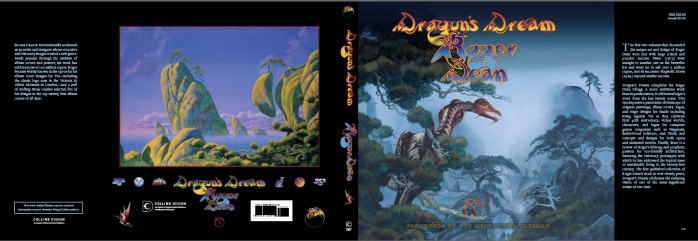

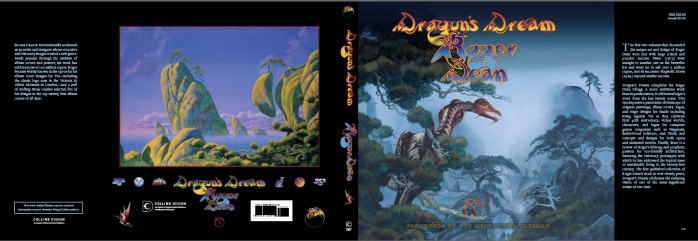

sent me, on the cover notes on ďDragonís DreamĒ, which is the latest

collection of your work. [The notes say] it completes the trilogy,

but was a trilogy always the intent?

ROGER DEAN: This is not a trilogy; itís just the third book. There might be

ten books for all I know, and I hope. I certainly have others in

mind; I certainly have others planned, so when I first saw that they

put trilogy on this, I was pretty pissed off with them. That was the

people at Ilex Press (laughs). I donít know why they did it. They

still use the word ďtrilogyĒ, and they insist I approved it, but I

think thatís bullshit. This is not a trilogy; itís merely the third

book in a series that hopefully will go on a lot longerÖnot my

thoughts and not my words. If it gets used anywhere, and it almost

certainly will, itís because I didnít catch it in time.

MOT: What do you want your fans and followers to know about this new

book?

RD: Well, basically itís completely new work; itís not a revision of

the old work. Itís completely new work; thereís more paintings in it

then in ďViewsĒ and ďMagnetic StormĒ put together, with a lot of new

work. Itís a much bigger book. If youíre into my work, you should

definitely buy it, because you wonít feel short-changed on this one

(laughs).

MOT: Does it cover a broad spectrum in terms of all your works:

stage sets, paintings, architecture?

RD: It covers all those things, yes. Mostly I wanted to focus in on

the paintings and the drawings. Having said that, though, itís a

very high proportion of my paintings. Itís probably 70% of the

paintings Iíve done between the last book ďMagnetic StormĒ [and this

book] coming out. Itís only the tiniest fraction of the drawings,

because Iíve got thousands of drawings. Iíve probably got four

thousand drawings, and thereís probably 20, 30, or 40 in the book; I

donít know. So I might do another book on drawings. In fact, I have

been in talks with people to do a series of publications of

sketchbooks, so that is a real possibility in the near future. That,

in itself, will stop this being the trilogy. Iíve got a lot of

design work too thatís not included. Some I just simply forgot;

others I thought Iíd save for another book. There just wasnít room

to put in all in. RD: It covers all those things, yes. Mostly I wanted to focus in on

the paintings and the drawings. Having said that, though, itís a

very high proportion of my paintings. Itís probably 70% of the

paintings Iíve done between the last book ďMagnetic StormĒ [and this

book] coming out. Itís only the tiniest fraction of the drawings,

because Iíve got thousands of drawings. Iíve probably got four

thousand drawings, and thereís probably 20, 30, or 40 in the book; I

donít know. So I might do another book on drawings. In fact, I have

been in talks with people to do a series of publications of

sketchbooks, so that is a real possibility in the near future. That,

in itself, will stop this being the trilogy. Iíve got a lot of

design work too thatís not included. Some I just simply forgot;

others I thought Iíd save for another book. There just wasnít room

to put in all in.

MOT: Youíre fairly prolific, and probably like most artists you tend

to sketch whenever the muse comes, so I would assume you probably

have piles of stuff in your home (laughs).

RD: I have a lot of stuff, yeah. Itís not all at my home, but I have

it. Of course, I put in some architectural stuff. I put in some

stage stuff. Unfortunately I didnít get a chance to put in the

finished opera stuff, which I thought looked great, but we had the

sketches in there.

MOT: I think one thing we discussed earlier was that this book also

contains some unseen paintings based on some of your classic Yes

works; unseen paintings like RELAYER, is that in the book?

RD: Yeah, yeah. There is a

RELAYER painting in there that has not

been seen before. I was going to put more RELAYER stuff, but I

didnít, because thereís quite a bit of RELAYER stuff thatís never

been seen--mostly drawings and other ideas (laughs). I even have a

little piece of a castle in the opera that looks a bit like RELAYER.

Yeah, RELAYER has had a much busier life that has ever been seen,

thatís for sure. Actually, thatís true of a lot of my paintings.

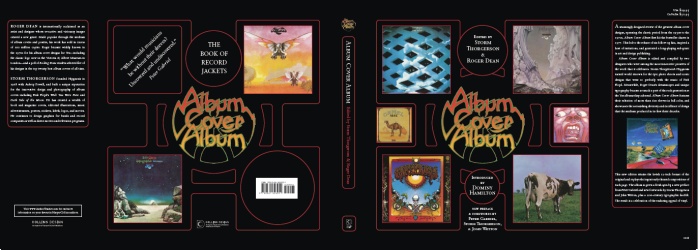

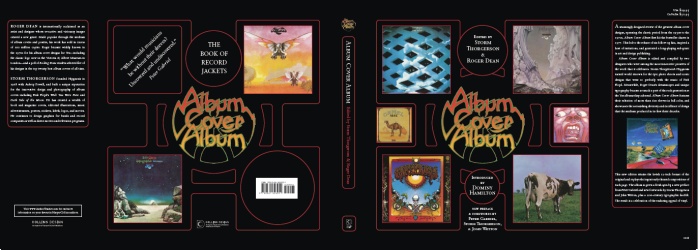

MOT: In addition to this new book ďDragonís DreamĒ, ďThe Album Cover

AlbumĒ has also been updated; in todayís age of downloading music to

your computer and artwork is no longer really part of the total

package, I was curious as to what was the intent of this book: to

capture a lost art?

RD: Yeah, I guess in a way it is a lost art; not really a lost art,

but a lost scale, a lost impact (laughs). A CD cover just isnít the

same thing, is it?

MOT: No, itís not, and you see CDs going by the wayside--as I said

you download music directly to your computer--and usually I would

think thereís probably no artwork associated with it.

RD: Well, what I think has been the tragedy and the idiocy is that

when the scale went from 12x12 to 5x5, record companies, instead

of thinking we have to work hard to give perceived value now, they

did the opposite. When Atlantic did CLOSE TO THE EDGE, for ten years

CLOSE TO THE EDGE was without the painting. And the message that

theyíre telling the public is that this is a piece of rubbish; we

donít care for it, discount it, disrespect it, basically. I think

thatís a tragedy, a shame.

MOT: Yeah, youíre right. For some reason when they first released

all those '70s Yes albums, they did it on the cheap, so you got just

the outside coverÖ

RD: Yeah, the inside printed in black and white without the imagery.

MOT: Or even without lyrics. Without the actual original packaging,

which they somehow rectified later, which was probably for them, a

canny move to create more revenue. If you already ran out to buy

CLOSE TO THE EDGE as a crappy CD version, now get it in the deluxe

CD version.

RD: Well, I donít think it would have created more revenue. Youíre

talking fractions of a cent to print the inside in color. It was

just a kind of tacky, really mediocre way of thinking, and it

explains why people bought Japanese imports, because they took a

great deal more care.

MOT: Yes, absolutely, the Japanese were the first to come out with

the little mini-reproductions. I have a few of those.

RD: Theyíre very nice.

MOT: Yeah, they were very, very nice.

RD: And hereís the thing--and Iíve said this a dozen times, so Iím

repeating myself--but the attitude of Japanese, whoís very much that

they honor the music; they honor the customer, and they treat it as

a gift. Music is a gift in every sense and so is the art. Itís a

gift, and it should be treated like a gift. It should be carefully

wrapped and packaged and presented. The way theyíve been doing it

[outside of Japan]--itís not a gift. Itís a tool, and a pretty

utilitarian one at that. Itís like giving someone a book token; itís

not the same thing as giving someone a book.

MOT: But do you think one of the problems with the Yes albums was

the fact that Yes probably didnít have ownership of their own work

at the time? Iím speculating here, because you look at some of the

other artists [who controlled their releases] like David BowieÖ

RD: I donít think that was the issue. The issue is that the US and

UK record companies did it to everything. It was just an attitude of

mind; ok, we can save 1.01 of a cent on every sale didnít mean much,

because it meant that the gross value of the sales was probably

down; it was just very, very, very shabby thinking, I think.

MOT: You donít think that the band itself somehow figured into this?

If memory serves, David Bowie held on to his catalog, but once he

released that to CD he made sure everything was perfectly right

about the releases. So he owned the catalog, he made sure it got out

there in the right way, and Iím wondering if Yes just didnít have

either the interest or the control to do the same thing.

RD: I canít answer that. I know that I was very distressed about it,

and there was no one I could address the issue with, particularly at

Atlantic. There was no sense of anyone giving a damn.

MOT: Going back to my core question about this updated version of

ďThe Album Cover AlbumĒ, what was the goal behind revising it and

putting it out there?

RD: Well, really there is a whole generation of people who are just

not used to album covers, not used to buying albums except in

collector stores and second-hand shops, and it seemed very

worthwhile showing people the best of what there was. Like anything,

you need a good history, and this was an excellent history, and it

had been out of print for a long time, so it seemed like a good idea

to put it back into print.

MOT: I think itís probably a very laudable idea too, and hopefully

itíll make some of these younger artists think about presentation of

their own product, because it goes beyond just the music; it helped

create a totality in terms of the presentation of the music.

RD: Itís a totality in terms of the story of the music; itís a

totality in terms of the culture of the music, and it is an attitude

of mind in terms of treating the music as a gift, a thing to be

honored. It is just a much more important thing than a few cents of

wrapping paper.

MOT: Itís just a richer experience. Iím not saying music alone isnít

rich, but it really contributed to the whole aural experience.

RD: Yeah, Iíve been talking about Atlantic, but Ahmet Ertegun and

the others whoíve founded Atlantic were very keen on doing it right

originally, but I guess they lost control as well, I donít know. But

in the end, it was a very distressing thing, looking at the way the

product was treated, packaged, and put out and marketed --everything

about it was distressingly mediocre.

MOT: I have a few questions about Yes. The front cover of what is

probably Yesí masterwork, CLOSE TO THE EDGE, is in retrospect,

probably one of your most unusual because itís not of anything.

There are no objects, there are no figures, there are no landscapes.

Itís really just a gradient of sorts. How did the concept for the

front cover develop?

RD: The idea behind it was two or three elements at once. First of

all, there was the brand new logo, and the other thing was to do, to

develop an idea that we tried and not done very successfully with

FRAGILE--to make it look like, not an old book, but a document. It

was an album; we werenít trying to make it look like a book, but we

wanted it to have some of that quality of a gold embossed book, so

the original idea was to do the lettering and have a gold embossed.

Naturally of course that never happened, which was a shame, because

it would have been great, and then as you opened it, there inside

would have been the picture, and it was also to bring people closer,

because the painting really you needed to look into much more. It

required a much closer scrutiny than the others Iíd done so far in

that it was much more gentle in its impact.

MOT: I was wondering if the inside painting had ever been considered

to be the front cover.

RD: Well, not in the sense of it being used as a front cover, but it

is kind of the symbol, the icon representing CLOSE TO THE EDGE.

MOT: I was one of those who bought the original vinyl release, and I

think one thing that did strike me that I found lost in later

editions is the outline of the lettering was very bright silver; it

really jumped out at you.

RD: Yeah, and then it was pretty much grey after that.

MOT: Yeah, just grey. When you mentioned the embossing, that

triggered that memory, because I remember (laughs) going and trying

to find another old copy of CLOSE TO THE EDGEÖI donít know if you

recall, but there was an Original Master Recording of CLOSE TO THE

EDGEÖ

RD: Thatís right.

MOT: Öand always looking at that, making sure that silver was just

eye-popping like it was in the original release.

RD: Yeah, it was a shame, I mean the least upsetting of the things I

wasnít happy with I guess. It looked pretty close to what I wanted

on the first release; not as dramatic as a gold-blocking or

silver-blocking, but still pretty good. I guess though the thing of

having it go out for ten years without the painting was insane.

MOT: Yeah, well thatís been rectified, especially in

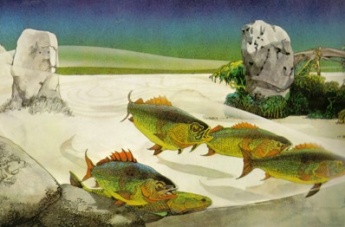

the Rhino re-release. I have a question about the painting for TALES

FROM TOPOGRAPHIC OCEANS, which is probably one of your most-iconic

as far as the Yes canon goes. One thing I noticed from reproductions of the cover thatís

missing from the original cover is the fish are in kind of a slipstream. You can

kind of see this path that theyíve taken, and thatís missing. I was

wondering what the story was behind that.

RD: Well, I never really liked it (laughs), and it wasnít part of

the painting. It was added after the painting. A lot of my paintings

Iíve had to do a little note, a mini-essay in my book to say that

over the years the titles of paintings have changed. There have been

a number of paintings which Iíve called something for a while then

thought it didnít really fit, changed it, and changed it again. And

a lot of paintings have changed too. Theyíve come out in one form,

and Iíve changed it, painted something out, painting something in,

so while theyíre in my studio, their names evolve, and the paintings

evolve, and thatís happened to a lot of my work, more than half, I

guess.

The one I use as an example in the book actually is the

YESSONGS painting with the mushroom city in the background, and in

ďViewsĒ you can see the catís footprints in the sky, but the cat

didnít just walk on the painting, and I tried to paint out his

footprints which clouds, but that didnít work, so they remain

visible, but the cat also at that time, maybe a week or two later or

a month or two later, but after Iíd have it photographed for

YESSONGS, he sprayed on the painting while it was standing against

the wall.

MOT: (laughs)

RD: So, I did warn him Iíd have to redo the painting, and I was

going to use his tail (both laugh). I did; I just redid the painting

then, so for years the painting really built a good reputation and

lots ofÖhundreds of people wrote to me about the footprints of the

cat across the sky and everything like that, but while the painting

was in my studio Iíd painted them out, and Iíd reworked the

painting, so for most of my life with that picture, which is a long

time--30 years itís been hanging around my studio--it looked quite

different to the reproductions of it.

MOT: So using that TOPOGRAPHIC OCEANS painting as an example, you

actually went back and you painted out the slipstream?

RD: No, I never painted it in.

MOT: Oh, then how was it added?

RD: I painted it on a piece of clear cellulose; we photographed it

in position, and we photographed it without it, and I preferred it

without it, so when it was used as a poster and everything, it was

without it.

MOT: Is that a technique that you use often?

RD: No, no.

MOT: Why was it added at all?

RD: An idea that Jon and I discussed. Jon was more convinced it

worked than me, and I tried it, but it didnít work, so I removed it.

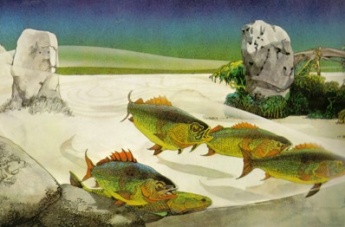

Left: TFTO album cover painting with slipstream;

Right: original without slipstream

MOT: Thatís a pretty cool insight into how you work. During the

'70s you had this long role with Yes, and youíve created quite a few

works with them until GOING FOR THE ONE. Did you ever create any

unseen artwork for GOING FOR THE ONE?

RD: No. I went out to Montreux, where Yes was recording, andÖI donít

know if they had the title GOING FOR THE ONE when I was out there,

they may have doneÖbut I think what happened there is when I got out

there, Jon was actually doing a painting that he wanted me to

incorporate in the cover, and I didnít think that would work

(laughs).

MOT: What, you would take his painting and incorporate it into your

own artwork?

RD: It happens occasionally that Jon had these conversations with

me, usually and fortunately heís very happy for me to do the

painting, but sometimes he has an idea. When he has an idea, we can

talk about it; but when heís doing a painting, it seemed like there

wasnít much scope for discussion.

MOT: Did that pretty much break off the relationship at that point,

or were there other conversations as to why your work wasnít used

for GOING FOR THE ONE?

RD: That was pretty much it, I think. Itís sometimesÖyou know, you

need a break (laughs).

MOT: What do you think of the artwork for GOING FOR THE ONE and

TORMATO?

RD: Well, first of all, in general, I think Storm Thorgerson (of

Hipgnosis, who designed the cover for those two albums) is a

brilliant designer; heís a good friend as well. Do I think thatís

his best work? No (laughs), and I do think that the figure in the

foreground [of GFTO] was absolutely a problem for all concerned.

MOT: You saw the billboard, Iím sure.

RD: No, tell me about the billboard.

MOT: When GOING FOR THE ONE came out, if memory serves, I think they

attempted to have the figure buck-naked as on the album cover, but

they ended up painting a pair of blue jeans on him.

RD: Really? I never saw that.

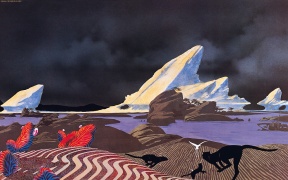

MOT: You returned to Yes with DRAMA, and that was really, for you, a

different piece of art for what was a very different album. Was that

stylistic shift intentional? MOT: You returned to Yes with DRAMA, and that was really, for you, a

different piece of art for what was a very different album. Was that

stylistic shift intentional?

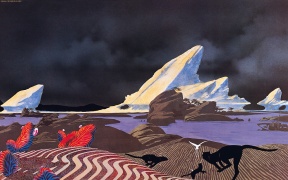

RD: Yeah, as much as any of these things are intentional. Itís like

when Iím working, I try to do as little conscious manipulating and

thinking about what Iím doing as I can and have it work as

intuitively as possible, so Iíd say that the DRAMA work was very

much an intuitive approach to how to do that cover. I was very

interested in having a very stormy sky; that was something I was

really interested in. I was very interested in the light playing

across the landscape, so there were some bits that jumped out and

very stark and bright, and other bits that are very dark--black on

dark grey. Yeah, there was a lot going on for me in that, and it was

like cooking I guess; I put in the ingredients and stirred it up,

and they came out in a way I guess that training and good luck

worked together.

MOT: It was very appropriate, given the title of the album. Did you

know the title of the album when you created the painting?

RD: Yes I did.

MOT: It is a very dramatic work. Did you have discussions with the

band as far as the content at all? One reason I ask is when I see

the cats running towards the birds, it evokes lyrics from ďTempus

FugitĒ, one of the songs on that album.

RD: Actually, I donít recall discussing those elements, but I did

discuss the boats, the ships in the desert; that was something Steve

and I had some discussions about.

MOT: Iím glad you brought up Steve, because that leads nicely to my

next question. It seems to me your strongest link to Yes is Steve.

Youíve created logo and artwork for both Asia, a band heís in of

course, as well as his own solo work. Can you talk a little bit

about your relationship with Steve?

RD: Yeah, I hope we get on. I certainly like working with Steve, but

youíve got to understand that Iíve done a few of his solo albums,

but I doubt if Iíve done half of them. Heís probably done more

pieces without me than heís done with me, but I do enjoy working

with him. Weíve got on, I guess now for, how long would it beÖ37

years; itís a long time. Yeah, I enjoy his company; I enjoy working

with him. For me, itís a nice, creative balance

2004 Stage Set - Left: without UV lighting; Right:

with UV lighting

Photos © 2004 Mike Tiano

MOT: Iíd like to move on to the 35th anniversary tour, particularly

the inflatables. [Roger designed the stage set for that tour.] As

you recall, I was there at the rehearsals in Yakima, and you were

still painting sets as the band were rehearsing, but one thing I

found really striking is something that I donít recall seeing after

those rehearsals, and that was the use of UV lighting, which really

transformed the set. Am I correct here that after those rehearsals,

the UV lighting was not used?

RD: No, it was used, not all the time. I was walking with the first

lighting designer, and he took a lot of time and effort to work in

my ideas, but we never had time. We just simply didnít have time; we

needed at least a week of rehearsal time to put together the

storyboard ideas that I had for the song list, and by the time he

decided he had enough and resigned, that was just before Madison

Square Garden. We pretty much worked on about half of the set, which

is a shame. I thought it was a real shame he left, because he

reallyÖwhen I work with a lighting designer, I divide the job into

three elements, is what I consider the basic default look of the

song, the primary color. Itís like Iím working on a canvas, and

thatís what I put my effort into, that default look, so that gives

the lighting designer scope to play around, as long as he refers

back to that default look on a regular basis. Does that make sense?

MOT: Yeah.

RD: So the third element is lighting the band. My default look is

lighting the stage, so the whole stage has a look that is particular

to a song; thatís what I try and work out, then how he plays with

that look with the music is down to him, and then how he lights the

band is between him and the band, so if you like, I work intensely

on 1/3 of the job, and the lighting guy has his area of freedom, but

he has another area where heís doing a pretty mechanical,

utilitarian job of lighting the band, so as I see it, thereís three

parts to that job, and we were working on the part that I just

mentioned to you--getting the default look that made each song

unique.

By the time he left, which was just before Madison Square

Garden, we had really made one good use of that ultraviolet light,

and I thought it was a pretty good use. What I was hoping to do and

was really pushing and pushing to get, was a much darker stage for

one of the songs, particularly ďSoonĒ. I liked a very dark stage for

ďSoonĒ, and we hadnít got there, and it was a lot of negotiations

with the band, because they didnít want to be stumbling around in a

dark stage. They wanted a minimal amount of light, so it was a

negotiating position we were in, and it was at

that stage where we

just really got the hang of using the UV light effectively when he

left, and the guy who took over for himÖbasically he wasnít

interested in my ideas (laughs); he just went off and did it

himself.

So I have to say at that point I felt this was a waste of my time

talking to someone who wasnít listening, so I didnít stay on and

work on beyond that point, so I donít know what happened. It was

very exasperating for me, because we didnít actually get the budget

to build the set until a couple of weeks before rehearsals. We

should have had it six months before, so a couple of weeks before

rehearsals, I had been telling the management if the funding for the

stage doesnít come by this particular date, youíre going to start

getting less or paying more, and of course it didnít come. And the

equation wasnít just getting less or paying more, it was being

delivered late, getting less or paying more, and in the end, all

three happened. They got less, some of it was late, and they had to

pay more. It was just irresponsible, from my perspective, but we

didnít get a lot of the main features of the set, the stage, until

the band went to Europe, in Finland, for the first time, all the

bits and pieces we designed were on stage at the same time, but we

werenít getting the lighting effects by then, so it was a bit

exasperating.

MOT: Hopefully things will go a little bit better with the 40th

anniversary tour.

RD: Yeah, I hope so. I have a very good working relationship with

[stage manager] David Wright, and fortunately heís going to be back

on this tour, and I like working with people who make my life easy,

and he does. He has the common sense and the contacts to make this

thing work, and he was very aware of the problems I was having on

the last tour with the lighting, and he said heís got a lighting guy

for the band in Canada who was interested to work with me on the

lighting, so hopefully that will all work out.

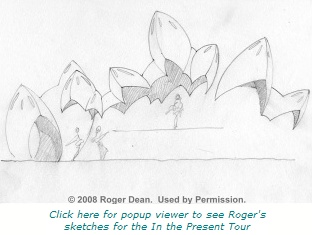

MOT: Can you give us a hint or indications of what we can expect as

far as set designs on this next tour?

RD: Well, itís not an inflatable; itís likeÖI was very interested to

add some gothic arch shapes, so I was looking at a kind of a mad

string of gothic arches, and theyíre made in stretch fabric, so itís

like a sail or a tent--stretch fabric on a frame, and a kind of mad

gothic arch.

MOT: Which I would presume would allow different lighting [depth]Ö

RD: Exactly, we can light the band, we can light the stage, we can

illuminate it from inside, from outside, and hopefully weíll have at

least some movement too, because the key to these things is to keep

the visual entertainment level high, and that requires movement as

well as light.

MOT: One thing I think gets lost in the concert lighting today is

everythingís always white. Everything is just bright, and I recall

the days where youíd have these intense color shifts, and some very,

very bold, bright colors, but it seems like now the goal is always

keep the band white, as like youíre filming every show or something.

RD: Well, thereís an issue here, and the issue is this simple: for

any color to look intense, it looks most intense on a black

background. If youíre in a very bright stage or in daylight, you

donít see the lights very well. So the lights get increasingly

intense the darker the stage gets. In addition, if youíre showing

RGB lights all on one spot, it comes out as white, doesnít it?

MOT: Right, exactly.

RD: Have a red, green, and blue light all on one spot, you get

white, so by putting too much color, you get white. That was one of

the problems with the stage after Madison Square Garden; there was a

misunderstanding, and Jon was looking for more color, but as they

increased the range of color, it got whiter, which is a natural

consequence of mixing too many colors at once on the same place, so

the issue about getting bright and dramatic color is definitely less

is more.

MOT: I think direction is always a big factor as well, because if

you have like a red coming from the very front and a blue coming

from behind, theyíre not coming from the same angle, so they donít

mix together, so you have more of a halo type of effect.

RD: Yes, or if you have them from the side, so theyíre on different

planes, so that is what we try to do. We try to have the facades

clearly delineated by light, and we could use different colors that

way. But you know itís complicated, and it takes time to set it all

up. Iíve been working on this opera initially, and they have very

simple lighting compared to rock and roll. Even so, it probably took

20 hours just to go through each act and point the lights, and make

them aim in the right place. It takes time, and it takes time to

rehearse and storyboard the lighting effects, hopefully weíll have

the time this time.

MOT: I want to go back to the 35th anniversary tour. Another

question I had was that some of the more cynical fans felt that Yes

were going kind of cheap with the inflatables. Obviously budget is

always a big consideration for the approach youíre going to take,

but I guess I was interested in your comments about why you took

that approach for that tour. It was strictly a budget or just

basically you had these ideas for inflatables that you wanted to put

forth.

RD: Well, there is quite a complicated answer for that. Basically it

works this way. Thereís two costs about the stage set. One of them

is building it, and the other is shipping it. And the inflatables,

no question about it, were cheaper to build and much cheaper to

ship. So there was definitely a cost advantage with the inflatables.

But thereís another issue as well, and that is that thereís certain

types of shapes that are particularly suitable to certain types of

processes. The fiberglass stuff we used, fiberglass can pretty much

do anything, but it takes a lot of effort to make it get good,

simple curves. We can get good, simple curves quite easily with

inflatables and stretch fabrics, so on this particular tour and the

last one, we are alternating between stretch fabric and inflatables,

because of the shapes they make. The primary reason for using

inflatables was because of the ease with which we could get

particular shapes; but there is a cost, you know. I understand that

U2 tours with a duplicate set, and they, on alternate nights, they

have alternate sets, so the sets leapfrog. Thatís an expensive

luxury; not all bands can afford that.

Roger with Alan White at 2004 Tour

rehearsals

MOT: Yeah. U2ís pulling in the numbers to allow that type of thing

to happen.

RD: Yeah, and Yes did once, but the thing about the set is itís

basically there to entertain and to look amazing, and I thought with

the inflatables, we could do all that.

MOT: In some ways it echoed the Crab Nebula set of 1976. I think if

I had to choose one Yes tour that I thought was the most

visually-stunning, it would have to be that tour. It was really one

of the most inventive stage sets of that era, with its intense

palate and the depth.

RD: I agree. I would agree with you in every way on that; itís the

one I thought was the most dramatic. Itís certainly the most weird

and it takes you absolutely into another world--most stunning. I

didnít have anything to do with that, though (laughs). That was my

brother. He did it entirely himself.

MOT: Well, itís a good thing to strive for (laughs).

RD: Yeah! Yeah, I mean..

MOT: I wish we could bring that back, because like you say just

mention the depth and just the palate of colors --it was just

stunning. I wish there was a good visual document of that tour; I

really do.

RD: Can you believe how much we do too? Thereís no real record of

that.

MOT: Which is a real shame. It was probably Yesís ultimate tour,

they continued to draw the numbers for a little while after that,

but thatís where they played JFK stadium and did all these gigantic

arena shows, so that gigantic set lent itself to that.

RD: They did film it, by the way.

MOT: Was it officially filmed?

RD: Oh yeah, I think there were six cameramen and a director, and

they filmed maybe a dozen concerts.

MOT: Oh really?

RD: Yeah.

MOT: What happened to that footage?

RD: Well, you know itís theÖfrom the Yes world, itís the big

mystery. Where is and what happened to that footage? I mean, thereís

a lot of it, thatís probably, I donít know, a 100 hours of film

somewhere.

MOT: Yeah.

RD: Somewhere someone has it, and I believe it was 35mm too, not 16,

so itísÖsomewhere thereís some good quality film of that tour.

MOT: Itíll show up in somebodyís garage or warehouse some dayÖ

RD: Well, that would be good. What would be not good is to find out

that it was scrapped.

MOT: Yeah, or to never find it again. So youíve been so

closely-associated with Yes, Roger, I had to wonder when you have

worked for the clients creating album covers and such, did they ever

convey any concerns, say something like, ďI donít want it to look

like a Yes coverĒ? (laughs)

RD: Well, one band in particular; usually people want it to look

like a Yes cover. Thatís a much bigger problem for me (both laugh).

I have to steer them away, but of course the one band who did

absolutely not want to look like Yes was Asia. In fact, they

didnítÖthey were very apologetic and kind to me and said, ďWe canít

use you to do the covers; weíve got to look totally different to

Yes,Ē and I said thatís fine; I understand. And I met up with Steve

one day when I thought it was all finished and put to bed, and I was

in the studio with him and they hadnít got a cover. They had maybe

half a dozen covers, but they didnít have one that was working for

them; and I said I could do your logo that was completely different

from Yes simply by making it very angular and sharp-edged, and if we

did something like a dragon--Yes had never used a dragon--so I said

that, and in two strokes, youíre completely different to Yes, except

that of course itís still me doing the painting. Anyway, I guess

thereís a combination of them thinking that might work and the fact

that (laughs) theyíd run out of time. I did it, and for me it

worked. I think the covers I did for Asia are still recognizably my

work, but nevertheless, completely different to Yes.

MOT: I thought it was interesting when made a comment you made

earlier that some artists wanted it to look like Yes, and I guess

one thing you donít want to do is be a derivative of yourself.

RD: Well, you know, people come to me, because they think itíll help

them commercially. Hopefully most people come to me because they

simply like my work, in which case I can do the best I can for them

without aiding and abetting them in looking like Yes. I usually

wouldnít do a cover for a band who was simply setting out to play

like and look like Yes; I donít think I would do that.

MOT: Got to be some type of challenge for you or some interest

beyond just getting a job.

RD: Yeah. Yeah.

MOT: Moving onto a different type of question: youíve designed quite

a bit of architecture in your career. I was wondering if any of your

designs were built and actually inhabited today.

RD: No, unfortunately no. Iíve got a commission as we speak for a

group of four houses, and I have a number of other commissions in

discussion--sorting out contracts and stuff. Iíve often had that,

and sometimes theyíve not comeÖtheyíve been cancelled, and sometimes

theyíve just been postponed, so Iíve got a number of projects which

I would say the client has on the backburner while they sort out

planning or money. These often take a long time; Iíve got, as I say,

one or two which I think could happen soon. I will make a huge song

and dance about it when it happens.

MOT: Because thinking back on ďViewsĒ you had some pretty unusual

designs for actual living space, and thatís why I was wondering had

any of these actually have been built and were inhabited and people

enjoyed being in that environment for long periods of time.

RD: What has happened is that I have been asked occasionally if I

would tone down the designs, and Iíve always said no, that would be

ridiculous. If someone asked me to do a painting and make it look a

bit more ordinary, I would simply say no. Why would I want that? The

two projects I have, which look as if theyíre likely to start in the

new year, the opposite is the brief. The brief is to go flat-out and

make it as amazing as possible, and that would be the decorative

detailing, and the interior is a psychological role for the shapes,

and they are as right as they can be now, but the decorative bits,

they can be very interesting and the pathways and the walkways

around the property give me scope for a lot of interesting stuff.

MOT: How much does technology play into this? I would assume you

would want your dwellings to be green in the sense that they be

energy-effective. How much do you think about that?

RD: We have terrific advantage over conventional buildings just from

the shape alone. They are much more energy-efficient than a

conventional building, regardless of technology--just by the shape.

MOT: So these are considerations that you think about when you

designÖ

RD: Very much part of my interest back in the

'60s when I first

started thinking this way, both be energy-efficient and not to use

toxic materials. I mean, when I was a student, I read Rachel

Carsonís ďSilent SpringĒ, and it gave me a terrific awareness of the

toxicity of a lot of materials we use in building and making things,

and I just thought I need to be able to design a house that uses no

toxic materials, and I think weíve done that, pretty much eradicated

the plastic and the toxic materials from the build.

View the photos for Edgar at

Il Sole 24 Ore

Photos © 2008 La Bottega dell'Immagine

MOT: So, winding down here, just want to talk a little bit about the

opera. I did find a website that had photographs of your work there.

This was a stage set that you created for ďEdgarĒ, a Puccini opera

that was done in Italy, and your daughter [Freyja Dean] was a

costume designer. I was just wondering how closely you worked

together, so you had a synergy between the set design and the

costumes, if there was any.

RD: Itís very funny, because as a child, she would be drawing away,

and Iíd say, ďHey, I can tell you how to paint that,Ē and sheíd say

basically, ďDad, leave me alone; I know how to do itĒ (both laugh)

MOT: Runs in the family.

RD: Sheís very young, 3-4 years old. I think in her whole life, she

let me show her how to paint an eyeball; thatís the only thing.

Everything else was, I mustnít interfere. So to get involved with

her painting--and I have to say that I considered it a terrific

advantage for her to have me to teach her, but she never wanted to

know (laughs); sheíd never take advantage of that--so I had to kind

of trick her, and it was like a big treat to her; if she behaved

very well, I would let her work on a painting with me, and from when

she was tiny, she worked on paintings with me. Iíve got a picture in

my book of her working on the background to the UNION album cover,

and she must be 2Ĺ-3 years old, something in there, and she painted

the whole 6í x 4í canvass blue, and all her brush marks are still in

the painting. You can still see her brushstrokes; I just used them

as texture, but I used them, and as the years went on, she would

always prime my canvasses, so she primed pretty much every canvass I

ever worked on. Maybe she put two or three coats of white paint on

it, and Iíd put one or two in addition, so itíd have five coats of

primer, sheíd put two or three of them on--as a special reward, I

wouldnít let her do that just for nothing (laughs). And as she got

older she did more and more of the painting, to the extent that I

did an album cover for Osibisa just this last few months, and while

I was working in Italy, they had some financial issues, because they

had new governments in Italy, and they didnít commission the costume

maker, so she was in England, not working on the opera, in the early

summer while I was out in Italy working on it, so she painted the

Osibisa cover for me (laughs), so itís gone from letting her do the

background to her doing the foreground and me doing the odd detail

now and then, so what can I say? She had worked with me.

MOT: Is this the first time that you worked with Osibisa, since that

original cover you did many, many years ago?

RD: No, Iíve worked on and off with them over the years.

MOT: Going through these photographs of your stage sets for ďEdgarĒ,

theyíre very striking, and again points to how lighting can really

illuminate the various aspects of the stage set, like Iím seeing

a building of some sort and in one photo

theyíre all blue with orange interiors, and then the next photograph

shows them like white with green roofs...lighting can

actually change a stage set.

RD: Yeah, thatís Act 1, and Act 1 starts at night and it gradually

becomes daylight in the act, so youíre looking at a night scene and

a daytime scene all within Act 1.

MOT: Well, itís very striking, and hopefully it was a success. Itís

still running now?

RD: Ah no, itís a summer festival, and itís over now; however they

did film it, so hopefully there will be a DVD available at some time

hopefully in the new year of the opera.

MOT: Oh wonderful. So closing on the Orphan Works act--Iíll provide

the background for our readers as to what this is, but my main

question for you is--has any progress been made regarding striking

this act down?

RD: Not that Iím aware of. I think itís a complete disaster. Itís

just about greed; itís about a bunch of big companies wanting access

to stuff they never made any effort or spent any money creating. It

will be very costly and very devastating for artists. It will be

very, very difficult to protect copyrights if it gets passed. It is

a complete disgrace. It serves no cultural, positive purpose

whatsoever.

MOT: Then, what was the intent in doing this in the first place?

RD: The intent in doing this in the first place is that two or three

very large companies make a lot of money selling art, clip art, and

this would allow them to sell a great deal more art that doesnít

belong to them that they didnít make and they didnít commission,

make a lot more money, and it would be at direct cost of all the

artists who created it. There is no reliable way of recording

artwork, and itís, as I say, a disgrace. Itís a cultural disaster

and a disgrace, but both American and British governments had the

fig leaf of saying it was the heritage purposes to protect things,

such as movies, that might disintegrate and not be rescued if there

the copyright act was preserved, but it would have been very simple.

It would have been ridiculous--no-brainer--to put it in a clause

in the copyright act allowing for heritage protection, the same as

they have a clause in the copyright act allowing for fair comments

by journalists. It was not a issue, and it was, as I say, it was a

pathetic attempt at a fig leaf to hide monumental greed.

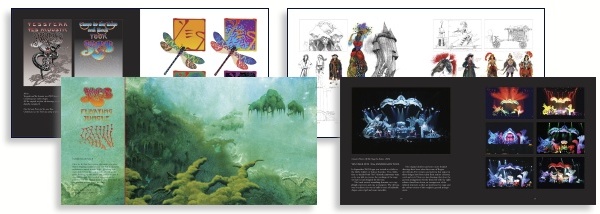

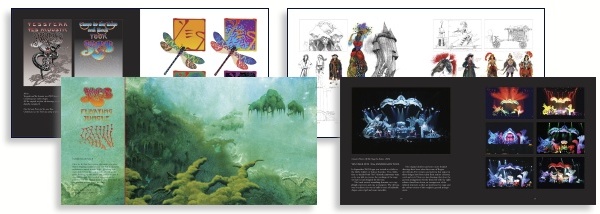

Pages from Dragon's Dream

|

RD: It covers all those things, yes. Mostly I wanted to focus in on

the paintings and the drawings. Having said that, though, itís a

very high proportion of my paintings. Itís probably 70% of the

paintings Iíve done between the last book ďMagnetic StormĒ [and this

book] coming out. Itís only the tiniest fraction of the drawings,

because Iíve got thousands of drawings. Iíve probably got four

thousand drawings, and thereís probably 20, 30, or 40 in the book; I

donít know. So I might do another book on drawings. In fact, I have

been in talks with people to do a series of publications of

sketchbooks, so that is a real possibility in the near future. That,

in itself, will stop this being the trilogy. Iíve got a lot of

design work too thatís not included. Some I just simply forgot;

others I thought Iíd save for another book. There just wasnít room

to put in all in.

RD: It covers all those things, yes. Mostly I wanted to focus in on

the paintings and the drawings. Having said that, though, itís a

very high proportion of my paintings. Itís probably 70% of the

paintings Iíve done between the last book ďMagnetic StormĒ [and this

book] coming out. Itís only the tiniest fraction of the drawings,

because Iíve got thousands of drawings. Iíve probably got four

thousand drawings, and thereís probably 20, 30, or 40 in the book; I

donít know. So I might do another book on drawings. In fact, I have

been in talks with people to do a series of publications of

sketchbooks, so that is a real possibility in the near future. That,

in itself, will stop this being the trilogy. Iíve got a lot of

design work too thatís not included. Some I just simply forgot;

others I thought Iíd save for another book. There just wasnít room

to put in all in.

MOT: You returned to Yes with DRAMA, and that was really, for you, a

different piece of art for what was a very different album. Was that

stylistic shift intentional?

MOT: You returned to Yes with DRAMA, and that was really, for you, a

different piece of art for what was a very different album. Was that

stylistic shift intentional?