MIKE TIANO: When did you first hear Yes?

LARRY GROUPÉ:

I heard TIME AND A WORD. I don't know what the year was,

but I heard it in my freshman year in high school, I think,

and really liked that. And of course THE YES ALBUM came

after that, and just confirmed the fact that I really like this

style of music, and every record from there just even more so;

so I was a fan early on with their stuff, and went and saw them,

because of where I was in the country, at the Philadelphia Spectrum,

saw a lot of their shows there, and have just been a fan since

day-one.

MOT: You heard the

albums as they were coming out, then? It wasn't after they were

already released.

LG: Yes.

MOT:

How did they influence you musically?

LG: Well, at that time, I was kind of deciding what

I was going to do with myself. I had taken piano lessons for

years, and was kind of enjoyed improvising my own music, but

was kind of tired of the lessons, and when Yes was happening,

I was really liking what I was hearing there and combined with

hearing Stravinsky's "Rite of Spring" from the music teacher

in high school, I go, "Oh my God, this is what I want to do.

I want to be an orchestral composer." And then my influences

were strongly from Yes as far as some harmony and rhythm stuff,

so it was a kind of a mixing of those two primary influences

that guided a lot of my improvisational work that I used to

do. And then one of these music teachers who would listen to

me in these practice rooms down the hall says you should write

some of those ideas down, which I had never done, and then I

go ok. So I struggled through the writing process and then realized

that I just loved what this was, and this is what composing

was all about, and I want to be an orchestral composer.

I

knew this when I was like a sophomore in high school for certainty,

and so luckily, which is unusual for high school kids. I knew

exactly what I wanted to do and then pursued that all the way

through my masters directly with no break, and because of what

I was doing and got better at that craft, I also thought that

film scoring would be the natural place to go. I didn't really

want to be a teacher in schools anymore; I had been in school

for so long at this point. I just wanted a change, and I go,

"Well, I'll go get my masters at UCSD down in San Diego and

that'll put me near L.A., and I'll decide for sure what I'm

doing." I basically started a family and stayed in that area,

and then my slow process of beating the pavement and doing things-getting

an agent and slowly doing some small films then bigger films,

and this has been that career path for my at this point. And

as that happened, culminating in doing "The Contender", that

had a good amount of notoriety, then I had heard about ten months

ago from today that Yes was considering putting together an

orchestral album and possible tour. I

knew this when I was like a sophomore in high school for certainty,

and so luckily, which is unusual for high school kids. I knew

exactly what I wanted to do and then pursued that all the way

through my masters directly with no break, and because of what

I was doing and got better at that craft, I also thought that

film scoring would be the natural place to go. I didn't really

want to be a teacher in schools anymore; I had been in school

for so long at this point. I just wanted a change, and I go,

"Well, I'll go get my masters at UCSD down in San Diego and

that'll put me near L.A., and I'll decide for sure what I'm

doing." I basically started a family and stayed in that area,

and then my slow process of beating the pavement and doing things-getting

an agent and slowly doing some small films then bigger films,

and this has been that career path for my at this point. And

as that happened, culminating in doing "The Contender", that

had a good amount of notoriety, then I had heard about ten months

ago from today that Yes was considering putting together an

orchestral album and possible tour.

MOT: How did you hear about it?

LG: I heard about it actually through an associate

at the San Diego Symphony, because they were approached as I

think the opening city, and they wanted to find out certain

costs and logistical information of using an orchestra. So for

whatever reasons of which I don't know why they contacted them

for these basic questions, but luckily they did, and I do a

lot of work for the San Diego Symphony. I am commissioned by

them to do original works for their seasons and things from

time to time... they're my community orchestra, and so like

all orchestras that need help, I help them with arrangements

on things and help putting thing together.

Since I was

a composer in residence to them in some degree, I simply knew

what was going on, and they had let me know that this had happened

and maybe I should call the management company. I go, "Oh my

God, I'm a huge Yes fan; I must call them." So, I did, and that

was a whole new set of obstacles to get through, and they said

who are you? Oh yeah, we heard of that; well, send us some demos

and we'll see. So, of course, weeks would go by with no word,

and then suddenly an email would come saying why don't you come

to the offices. We want to talk about the logistics of orchestral

recording and so forth, and so I'd come up and have a couple

of meetings with the management to that effect.

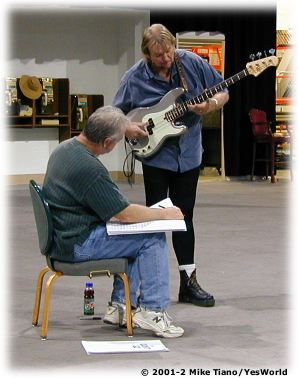

One time Chris Squire happened

to be there unexpectedly, so I had a chance to meet him, so

we had a small meet-and-greet in that regard. And again several

weeks would go by with nothing from those meetings, and then

suddenly I got a call... management calling and saying, "You

know, why don't you go up to Santa Barbara. The band would like

to have you hang out and see more of you and talk to you." And

then I had also prepared more demos for them of things that

I had written that would hopefully interest them and me, and

still no response, not knowing where I really stood; and then

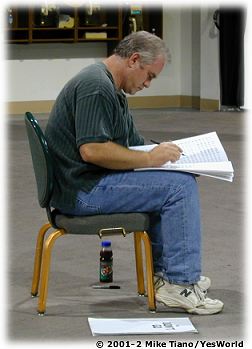

I went to the Santa Barbara sessions, which were just beginning,

and stayed there for a couple of days.

MOT: What were these demos that you had

written?

LG: Just other pieces

that I have done for orchestra, film pieces, I just took a collection-made

a special mix of them and sent them on. Knowing what the band

was like, I said if they were going to be interested in me,

they should hear these pieces, and so I put together my own

custom demo of existing work and sent those on, and then I went

up to Santa Barbara for this visit. I stayed there a couple

of days and just absorbed their process in the studio; and when

I had left, I took with me a DAT of three of the current tunes

they were just putting down the skeletal structure on, and I

said how about if I take these and I will then make elaborate

orchestral renderings with my high-end digital studio at home

and show you what could happen with an orchestra. And they said

that's sounds like a good plan, so I went home and I spent a

week doing that, in some cases writing huge three minute overtures

before the tunes even occurred and then putting on the orchestration

like I just said and making these things as presentable as possible,

and got on a plane and flew back up a week later to present

them.

At the time, Steve and Jon were the only ones

currently in the studio that day, and so I waited for a moment

in the afternoon to finally sit down and play these in the control

room and played through like all three of them, and like they

were very quiet and sitting motionless. I had no idea how this

was going. I had decided during the creation of these things

that I was going to do whatever I felt what was right; I wasn't

going to try to guess what they wanted. I wasn't going to try

to play it safe and just kind of be in the background. I just

went right on top of it, in the way that I felt this is what

I would do if I could do anything I wanted to be really part

of this from a deeper, compositional level and not just come

on as sweetening later on top of their tracks.

I didn't want to do that,

so that was my approach, so I was really concerned. Either they're

really going to like this or they're really going to hate it;

at least there won't be anything in the middle, and I'll certainly

know whether I'm working with them or I'm out of here. It'll

all happen right now, so we had that playback; and they loved

it. Jon really, really liked the material, was very excited

about it. Steve was very impressed with the way the renderings

worked but was very concerned about how it was going to affect

his guitar parts and other aspects and how it was going to fit

in in general, and that began what was kind of a polarization

for Jon and Steve in what they should do with and without orchestra.

Jon very much wanted to move

ahead with it; Steve wanted to be far more careful about it...

if it was a film, it's like having a film with four directors.

Everybody eventually had their input on the stuff that I did;

they were all basically excited and thought I was the right

guy, so that at least solidified me into the job, and now the

phase of what do we do-how am I going to accommodate these different

comments, but at the same time still have me in there the way

that I want to do it, otherwise I'm just being a hack. I don't

want to do that, so ultimately I just ended up doing what I

wanted (laughs).

It was really the best answer, and

if there was something that really didn't work for them, obviously

I would change it, and I did and I have when there were sections

that should change, otherwise I think they were actually happy

and found it probably best that I just came in and did my thing.

You know, it seemed to be working; let's not change that process,

so I continued through the whole record in this way doing what

I felt really would make a difference, and then when there was

something very specific that needed to be changed, then I would

do that, but I'd say 95% of the original writing stayed intact.

MOT: So basically you created everything

from scratch yourself...

LG: Yeah.

MOT: ...almost

like another member of the band, coming up with your own parts.

LG: Right, except I would go home and do it, because

I'm writing this stuff. I can't just sit at the piano and show

them the ideas. I need to experiment and work these things out

and make these things an orchestral, symphonic experience, which

is something you can't do directly at a keyboard, because that's

only a single approach.

I'm obviously an orchestral

writer, and there's counterpoint and there's all kinds of things

that are happening. You can't just simply play all that stuff;

you got to write it, in my case, put it in the computer and

render it all so that the band can respond to it, so I gave

them... you know so they knew what was coming.

MOT: Initially when you did the demos,

did you handle the parts by keyboards or did you have actual

players come in and play the parts?

LG: No, I did everything on the computer system to

show what the rendering would be, waiting for our actual live

recording sessions. The reason I rendered them so thoroughly

was so they'd know what it would sound like when the real orchestra

came in, but I didn't bother to go in and certainly hire and

record various players to show. It wasn't necessary; the renderings

are so apparent in what they are going to do that it takes all

the guesswork out.

MOT: To be

clear, what would I be hearing if I heard the rendering?

LG: I take their recorded mix; I put it in my hard

drive, so I can play it back on my sequencer and hear the actual

recording, and while I'm live with that I can slowly put in

all the different parts that the orchestra is going to play,

playing back on all my samplers that contain the strings and

the woodwinds and the brass and the percussion, so I have all

those instruments represented in my system, and then I dress

up that recording with those written orchestrations.

MOT: As far as orchestrating the actual

album, it sounds like you had a lot of creative freedom.

LG: Yeah, I'm a co-composer. I don't know if they

would see... I think they would agree to this, I don't know

to what varying degrees, but I see myself as a co-composer on

the record.

MOT: But there's

little input in terms of what you've actually written...

LG: Yeah,

comments that would come back... if I wanted to put the seventh

in or something, or actually what I would do is introduce more

dissonances, and that's where a lot of the interests, and sometimes

some of the concerns, came from. I'd have to soften certain

things that I did-go after harder on other things, just given

the reactions that they had. I think the band wanted to hear

me do more of what they were doing, like a doubling. I'm going

doodle doodle doodle doo, and Chris might do on a bass line,

and he was kind of hoping to hear the orchestra do more of that

with him.

I actually saw the band more as the soloist

like a concerto, where they're the ones out front, then I'm

doing things that are behind that aren't what they're doing,

specifically those are their lines. When it came to the tour

there are differences in the tour, especially in the classic

songs I did much more of the doubling because those are the

lines that people are knowing and expecting, and in the record,

there's a lot more counterpoint and different harmonies coming

from me in the recording.

MOT:

One of the hallmarks of Yes is having counterpoint and having

a melody or something that came into the song reemerge later.

Did you incorporate that...

LG: Like if Chris

has an ascending line in the recording, I almost invariably

will do a counter line against it, as opposed to with him, which

is something I would do in the classic songs for the tour, but

in the recording I take that material and then I react to it

as if it was something new as opposed to copying it in the orchestra.

MOT: But would you bring back themes?

LG: Yeah, absolutely. In "Deeper"-I keep calling

it that-"In the Presence Of", there's a line that I wrote in

there that continually recurs throughout the piece which Jon

really liked just because there's a certain continuity to the

length of the piece by having that, and having these things

return I think is of value in having the orchestra there.

MOT: I think what's interesting

about "Deeper" is where there's that one section in which you

go [sings orchestral swells] I think "Mellotron" right there.

Is that conscious?

LG: No, but I am making a wispy effect that could

be done by Mellotron. I'm not trying to emulate that by any

means.

MOT: I ask because one

of the key points about this album was that the orchestra was

going to take over for the traditional keyboard.

LG: Yeah, it certainly did. There is no traditional

keyboard part outside of a piano solo here and there from Alan

or something, but beyond that, it absolutely does that, but

of course it goes beyond that because I've got an orchestra

literally at my disposal, as oppose to... I mean to work it

out from a keyboard perspective would be a different set of

parameters, I mean to actually insert the orchestra there, replacing

what the keyboard did is true, but that is part of the job.

Of course, it is far more magnified as it were, because I've

got this orchestra here, so certainly I find the keyboard situation

more confining, if I was going to come in as a keyboardist on

the record and far more opened from an orchestral perspective.

MOT: Were you in on the decision

to actually bring in a keyboard player...

LG: We talked

about it. Originally the tour... it started with, "Well, obviously

we won't have a keyboard player," because the orchestra is doing

those roles, and that's why I was very conscious when we were

doing "Close to the Edge" and "Ritual". Whenever the Mellotron

strings would come in, of course I'll be doing strings there,

and I am doubling certain lines, but also I'm going beyond that-I

take the orchestration further whenever I can, so it was a multi-phased

decision on the keyboardist.

First, we don't need one because

the orchestra's doing it; then as we realized, wait a minute,

if we're doing "Roundabout", if we're going to have the famous

keyboard solos in "Ritual" and "Close to the Edge"-all the things

that happen on B-3 Organ or Moog, they should be. I mean, there's

no reason for me to write those awkward passages that are so

obvious and easy on keyboard to give them to the trumpets or

the violins. Let's not even bother. We should have somebody

do that; there was even, at first, discussion about me being

that person, because they thought it would only be occasionally.

Then

the second option was, "Well Larry, how about if you jump down

from the podium and play these few, but famous keyboard parts?"

I go, "Well, I guess that could happen." Then, as we churned

that around for three or four days, I call them up and I go,

"You know, that's not going to work. I can't leave what I'm

doing here; you need to get somebody, even if it's just specifically

for those bits," because they had no idea what the songs on

the tour really were going to be yet, so we were talking still

conceptually, so given that final determination that we need

to have somebody, at least for the solos that people know is

what then afforded us... then found Tom Brislin and ultimately

hired him, and he's incredible, and he's doing so much more

that what that was. Then

the second option was, "Well Larry, how about if you jump down

from the podium and play these few, but famous keyboard parts?"

I go, "Well, I guess that could happen." Then, as we churned

that around for three or four days, I call them up and I go,

"You know, that's not going to work. I can't leave what I'm

doing here; you need to get somebody, even if it's just specifically

for those bits," because they had no idea what the songs on

the tour really were going to be yet, so we were talking still

conceptually, so given that final determination that we need

to have somebody, at least for the solos that people know is

what then afforded us... then found Tom Brislin and ultimately

hired him, and he's incredible, and he's doing so much more

that what that was.

Tom Brislin was brought on, I guess

still with the understanding that it might just be a smaller

role. They weren't really sure until the tour tunes were ultimately

picked, and then Tom of course kicked in in Reno to go through

the rehearsal. He's far more involved, you know doing certainly

the famous solo parts, but also just supporting general keyboard

parts that were always in there that needed to be there, whether

they were featured or not; like in "Gates of Delirium", the

opening [sings part of the opening], that's not necessarily

a solo, but it's just part of the fabric of what the tune is,

and I'm doing other things that support that as well, and he's

also singing and doing all kinds of stuff, so I think Tom Brislin's

role is a much larger role than ever anticipated. And I think

I myself, and I'm sure the band feels, is just they're lucky

to have him. I think he's incredible; I really do think he's

an amazing talent. Given the fact that he's 27, he's going to

be a big deal in like five years.

MOT: Is he playing any Mellotron or string-type

parts in tandem with the orchestra?

LG: Every now and then. He's taken the time to know

basically what I'm doing, and if we're... and I can only put

this in a blunt way... if we're in a smaller town when the orchestra's

not as strong as the bigger city orchestra, then he will kind

of assist; if it's going to get a little tough or a little bit

sour or if the strings are a little weak and they're not sure,

you know there'll be someone to help. He's great about doing

that.

MOT: Why don't you explain

the process for what happens before each show.

LG: You mean

the rehearsals?

MOT: Yeah, in

terms of the musicians getting the scores... do they get it

in advance?

LG: Everybody asks

that. No, first of all, we don't have enough copies that can

be sent around in advance like that. All the scores and parts

are right on the tour buses and so, they don't arrive to the

venue until the moment that we do, because most of the orchestras

are pick-up orchestras, which means they're hired by a contractor

in each city, and they're not necessarily a working group, unless

it's a big city like Vancouver-it's the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra,

or San Diego Symphony Orchestra, so forth... the Hollywood Bowl

Orchestra and Atlanta, will probably be the last only cities

that have that. All the rest, even Seattle, even though the

Seattle Symphony is here, that particular venue out at the Winery

is still not part of their normal pop season, so it's a pick-up

orchestra that's hired by the contractor, so the music won't

be disseminated to the players through a librarian, which normally

happens in an organized symphony.

So even if we did have

the parts in advance, they simply probably wouldn't get to those

players because they're hired, usually one or two days before

the show, so there you have it. They never see it; they see

it at 3:00 when the rehearsal happens. It hits their stands;

they show up and they see it for the very first time that afternoon,

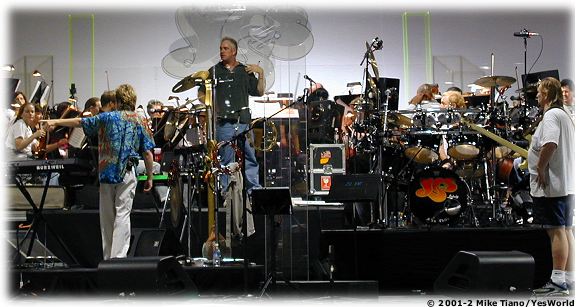

and then because they only have normally a two hour rehearsal,

I will jump through the charts in such a way that I just go

over the high spots and the most difficult passages, never playing

the whole song and get through everything so they've had a chance

to read it at least once, and then we have a dinner break, and

there's the show, and then you hope for the best at that point.

MOT: Is there always a rehearsal

in every city?

LG: Yes, there has to be. There is no way we could

go on without one; it would just be too high-risk. If they've

never seen it and they play it, boom, there it is. It could

happen, but it would be I think riddled with problems, because

of all the tempo and other changes-the complexity of Yes' music,

you simply just can't read it cold. If it was something like

a real simple pop ballad in 4/4 that just never changes it's

scope at all, you could probably get away with it if the parts

were absolutely impeccably accurate.

MOT: So, those gigs where Yes were also rehearsing,

that's separate, I take it? Like at the Hollywood Bowl, both

the band and the orchestra [were rehearsing together]...

LG: Yeah,

the reason why that happened is-well, two reasons. One, they

still wanted to work out "Don't' Go" and "In the Presence Of",

because they still were trying to get their stage understanding

of the tune on it. It's different when they're going back to

songs twenty years ago; they have those down, but actually the

newer songs I think are a little bit more tenuous for the band,

because they just haven't been used to playing them that much.

The second reason why they sometimes rehearse with us is that

they have limited sound check time, and they have to go on when

we do, but otherwise they do not rehearse on a daily basis in

that regard.

MOT: Speaking of

the new pieces, I heard a comment you made that the new pieces

were the easiest to play live.

LG: They are. They're

the easiest to play for the orchestra, because those particular

chosen numbers are the ones that actually do stay in the same

tempo all the way down. They have very little variance... you

know as far as what's coming around the corner. Stuff like "Close

to the Edge" and "Ritual" and "Gates" of course, every four

to six bars there's some new event that's happening or we're

changing this to here, and now the feeling is fast or slower,

I'll conduct in 2. I'll conduct in 7. I'll do this; I'll do

that. Those are the things we work the hardest on the rehearsal,

but don't go in deeper... just had to be songs that, as far

as what we're doing are much simpler, so those are usually the

easiest to play.

MOT: They're

fairly straightforward as opposed to different time signatures

like "Gates of Delirium". Let's talk about some of these older

songs. How did you approach orchestrating them in terms of what

the orchestra played... how do you decide whether to create

something new and original to enhance the music as opposed to

taking the original arrangement to maybe just aping the keyboard

parts.

LG:

Right, let me answer that by also talking about how I approached

the record, which is different than the tour. In the record,

I definitely was doing things that were not mapping over what

the band did; I was doing more new things, adding different

harmonies, Moog counterpoints, putting overtures in front of

pieces-far more compositionally involved as a fifth writer to

that record. In the case of the tour, especially the classic

pieces everybody knows, I had two jobs basically. One was to

certainly replace things like the Mellotron and things like

that that used to be what would certainly represent what strings

would do, but since I have an orchestra at my disposal, I can

make those parts grander, more elaborate than what the original

keyboard parts were, which were basically just whole notes many

times-just holding down chords.

I'll have moving lines running

through those now, because I can, because I have this orchestra

at my disposal, so in one sense I am replacing what those keyboard

parts were and elaborating them, because I have the ability

to do that with the orchestra. Secondly, I would add some new

and different things wherever it made sense to, without upsetting

the primary structure, so I follow more of the band in the original...

in the older material for the tour, but I don't do that in record,

where I'm coming in far newer.

MOT: I think it would be an obvious thing

to open with the "Firebird Suite" with the orchestra, since

that piece is so famously associated with Yes.

LG: Right.

MOT: Why did you and/or the band

decide not to do it?

LG: We took the overture

[from "Give Love Each Day"], which is much shorter but it's

still there acting as an overture for the band, from the record,

and of course it makes complete sense at this point to go ahead

and use that, because that's now available. Pointing towards

the new MAGNIFICATION CD so it made complete sense to

put that in there. Even though we don't know it yet, there it

is, so that has in essence replaced the "Firebird".

MOT: I was curious why or how you composed

the introduction to "Long Distance Runaround". I saw it as almost

being fanfare-ish, and I thought how come you didn't have staccato

themes, or even use some of "The Fish".

LG: Sure, that would

have been cool. So, you're talking about the overture that precedes

that one, yeah. It's an odd set list for me in the beginning

only because we have the main overture that goes into "Close

to the Edge", and then suddenly we have second overture that

goes into "Long Distance". This has to do with the reshuffling

and now settling of what the set list is. It used to be that

that overture is at the second half, after we came back after

our break from "Gates", we take this break, and we come back

onstage, which is in essence the second half, and then that's

where it used to be is we'd play that little overture there,

and then it would go into something else, so Jon just preferred

it being an overture to "Long Distance", and then they've moved

it forward in the set list, so it's kind of in an awkward spot,

and it wasn't written to tie into "Long Distance". If it was,

then I think you're right, having little leitmotifs that were

kind of indicating this is coming would have been a really neat

idea, but that's not what it was designed for. It was actually

designed as the very opening number, as a way to begin the show,

that we would play that.

It's more fanfare-ish like

you say for that purpose, and then the end was written in such

a way that it wouldn't recycle and repeat, and then the band

was going to come out as they do and then pick up their instruments

and actually start jamming along with this chord progression,

and then we would just simply go into "Close to the Edge". It

would just melt into that, but Jon wanted changes. "No, I want

you to do the overture from this part of the record as the opening

thing-we'll go to 'Close to the Edge'", so then that replaced

itself there. And then this overture temporarily led in the

second half, then it went into "Long Distance", which is why

a little bit askew, and perhaps that's actually moved up into

the set list, so it's just a matter of reshuffling the deck,

and that's where it's now ended up.

MOT: It's too bad it didn't come to fruition,

because that's a very, very intriguing idea.

LG: Yeah, I thought

it would have been very cool, because it would have just come

into the orchestra-this handshake with the orchestra would have

occurred, and then we go into "Close to the Edge", but I didn't

ask reasons why. I didn't want to do that, but they ultimately

didn't want to do it.

MOT: What

were you saying about that introduction overture isn't on the

recorded version that you did for the band-the orchestrated

"Long Distance Runaround"?

LG: Right, the overture

that's in front of "Long Distance" is not on the record. It's

not anywhere. I wrote it originally just as a show opener for

this tour; now it simply has changed its role.

MOT: I noticed during the show that

the orchestra has earpieces, and you're talking to them. What

types of things are you telling them?

LG: You know, complementing

them on their clothes and asking about the weather and what's

around... no, all it is is just what it appears to be. It's

just a direct line of communication to the orchestra, because

the band will sometimes add an extra chord, not an extra chord

but an extra measure, and the band of course knows how to work

and flux amongst itself, like, "Oh, we're going to slow this...

I know Steve's taking an extra two bars," or Jon's come in early

on the vocal. These things happen in the course of the show,

and the band of course can react to that immediately, because

that's how bands react, but of course it's totally different

for an orchestra that doesn't either know the music or they're

slaved to the page that they're reading, so they're absolutely

going in a certain way.

So as soon as I hear something

like that happening, I get on the mic and explain "OK, we're

two bars behind the singer; we're going to move forward to bar

364... now," and then I queue them into that, and then we shift

into the right spot as soon as I have a chance to collect myself

and find where they are, so that's purely for those reasons

when things happen, or for resting for four bars, I may explain

how the next entrance is going to work, reminding them about

something that we learned in rehearsal, because there's so much

that's going on. They're not going to remember everything, and

it's just a way of aiding that communication with what's going

on onstage.

MOT: And you take

a lot of your queues from Alan...

LG: I'd say probably

80% are from Alan and then 19% are from Chris, and then the

remaining 1% is either from Tom the keyboard player I watch

Steve or Jon, not that they queue me, but I watch for things

that they're doing, but primarily Alan and Chris for major changes.

MOT:

I don't know if you could speak to the financial challenges

of the tour. MOT:

I don't know if you could speak to the financial challenges

of the tour.

LG: If they had the

money to allow principles like a concertmaster and principle

horn and trumpet, that would be really great, but I mean it

is expensive to have people go and travel with you, so that's

where their expenses lie is in weekly salaries plus travel accommodations

for people that are going on the tour, which is plenty of us

going already between the crew and the band. So to add four

to six more, which is my original request, to have the principles

of the orchestra go with us that hold down these particular

key positions and would have the music down cold. It would be

a better thing, but it's just a matter of money, and then I

actually said no, we're going to have to go for it and hope

for the best.

MOT: My thought

was that having to use pick-up musicians and local symphonies

is probably pretty expensive in itself.

LG: Oh yeah, I mean

the simple hiring of the orchestra alone-the way we're doing

it now, is just huge, so yeah, all these things cost a lot of

money.

MOT: Do you plan on publishing

any of these scores?

LG: Well, I mean they're

not mine to publish. It is property of the band; that's my agreement

with them. As far as the writing, it's theirs at this point

from this point forward, and I certainly hope that they will.

They'll probably put them in a book format or at least get them

on the Internet, so I mean people have asked that. I'm sure

that that will happen when the time comes to do so.

MOT: I've been asked how to get a hold

of scores for orchestra that people want to play, because Yes

music is so challenging, and I think that they want to actually

try that with a proper orchestra.

LG: These orchestrations

are written specifically for the tour, so they might have empty

spots in them. If you were to play these arrangements without

the band, it would work sometimes and not work others, because

certain parts I leave for the band, because we're doing embellishment

over here, so it'll be a little odd. It's expected that the

rhythm section or "the band" is playing.

MOT: How many pieces in the orchestra, by

the way?

LG: Well, it's now reduced to 44, because of the staging

requirements. It started at 50, and we've had to drop six for

staging. Some of the bigger cities, like Hollywood Bowl, we

had up to 60 expanded strings, which was wonderful, so it's

all based on the venue and the staging that's available.

MOT: What do you use?

LG: String section,

because everybody else-the four horns, the four trombones and

three trumpets, and the five woodwinds-I mean they all have

very specific parts. You can't really drop any of them. The

strings are duplicitous of course, just for power and numbers,

so if you have to drop people, it's going to come out of the

strings, and that makes is harder to get the impact and huge,

lush sound, but that's what you have to go through.

MOT: Have you been fairly satisfied

with the results of the performances?

LG: Yeah, all of them-Reno

included, not that I was expecting it to be bad, but I was just

concerned that the first show would have all kinds of problems,

but I thought it was surprisingly successful, so and all of

them have been very, very good, so I've been very happy with

it.

MOT: What are the high points for you during

the show?

LG: Actually, what used to be my fear was "Gates Of Delirium",

and is now my favorite thing to do, because it's just so integrated

with what's going on with the band. I just enjoy hearing that

one go down, and my bigger concerns are "Ritual" during the

percussion breaks, just because we still have these areas that

are difficult to get out of, but they're working now, so I think

everything's seems to be intact.

MOT: When you say "Gates", are you referring

to a specific section?

LG: Yeah, pretty much

the middle section where all the complex rhythms really get

in there. I now fully understand them, and we're executing them

just perfectly, so I'm really happy with that, and they're fun

to play because there are huge sounds right there.

MOT: Yeah, the intro is a challenge

too.

LG:

That's still a little bit hard, because Jon's vocal entrance...

we're never really sure where that's going to be, but that's

one of those areas where we do jump forward or jump back as

necessary, but it's not too bad. "Nous Sommes Du Soleil" out

of "Ritual", Jon has a tendency to come in where he likes to

come in. It's not a problem for us to do it, because it's just

a matter of paying attention and jumping around. It always works,

but I don't mind that. It makes it kind of fun to, "OK, let's

move back two bars or move forward four," and everybody's perfectly

happy with that.

MOT: There

are some sections where you're not afraid to jump in, like in

the beginning of "Gates" where Steve goes [sings the fast guitar

figure, at 1:38 into RELAYER]. I'm surprised to hear the orchestra

playing that part.

LG:

Well, I mean they do play these parts rote, and they're absolutely

where they are, and I know that they're going to play them,

so why not take advantage of them... yeah, that's a part of

the fun of making it a more complex orchestration on those things,

because you might as well go for it. That's what Yes is all

about, so we're going to be about that too.

MOT: Did you ever hear THE SYMPHONIC MUSIC

OF YES?

LG: You know, I never have. I just don't happen to have

a copy, and I've been very busy. I wanted to hear it, just so

I knew what had happened before, but I've never heard it.

MOT: That's pretty much not

appreciated by most Yes fans. They thought it was kind of like

a hack-type of job.

LG: Was it? I don't

have an opinion only because I haven't heard it, so... well

hopefully this will be better, I'm sure... I think it is. The

reaction that we've been getting from the fans on the Internet

seems very positive, so I think it's a winner.

MOT: What are some of your favorite

Yes songs?

LG: "Close to the Edge"-one of my all-time favorites,

the whole album and everything on it... "Siberian Khatru"-I

love that. "Heart of the Sunrise"-maybe my personal favorite.

There was discussion about possibly doing that, but that just

didn't happen. I mean, there are so many different choices,

and almost every one of them works for orchestra. It's just...

it's incredible. There's so many that I'd like to do. There's

even "Time And A Word"-I like that.

MOT: A lot of people were hoping for "No

Opportunity Necessary". That's a heavily-orchestrated song to

begin with, and that's almost fanfare-ish. Yes hasn't played

that in years.

LG: It's not that they wouldn't; it's just that they

make their choices, and then they have to spend several weeks

working those back up again, so it's a matter of their original

choice list.

MOT: I was going

to ask what Yes song would you like to do the most. It sounds

like maybe "Heart of the Sunrise".

LG: I would have loved

to have done that. I just love that tune, and I love Bill Bruford's

drums in the whole beginning of it, but I'm just... he's so

melodic in that opening thing. It's great to follow that, so

that would have been interesting to find a way to potentially

orchestrate that with drums. That would have been a really interesting

thing to do, and I know Alan would be happy to play that part

to the letter if we ever got down to doing it, if they wanted

to work that song back in, but it's not part of the plan.

MOT: You're leaving the tour now;

was this due to commitments you have before the tour?

LG: Yes,

it is, and it's a double-whammy for me, because it's a new HBO

series, and I'm the composer on, and they weren't intending

to go into production until the fall. They had already written

the pilot and the first two or three episodes back in the spring,

just to initiate the series, and then they were waiting for

their appropriate schedule to go into production. HBO loved

the first three episodes so much, they've advanced it, and now

the show will air and start airing in September, so now we have

to complete the rest of the episodes in the month of August,

and that came down over the last three and a half-four weeks,

which was crushing, because it laid itself directly over the

top of the tour.

MOT: Can you

divulge the name of the show?

LG: Oh yeah, it's

called "The Mind of the Married Man". It's a new comedy series

for HBO, and it's... I could loosely say it's the male version

of "Sex in the City". You could look at it that way. It's not

exactly that, but that's the simplest way to put into one sentence,

but because they advanced their production schedule, and I'm

contracted to be the composer on it, I have to fulfill my obligation

and write these episodes and record them and produce them, unfortunately

all throughout the month of August, and it's just... it was

terrible when it happened because I want to be on the tour,

and I don't like leaving. I don't like putting substitutes into

the conductor position, even though I feel the people I found

and have worked hard to get, I'm sure will be fine.

I'm not particularly worried that there's going to be any problems

at the show, but I just don't like changing horses in mid-stream,

primarily I'd simply like to continue with the tour. I mean,

I've worked my ass off to do this, and suddenly I'm not getting

to do the fun part, and that's to go onstage and play the stuff,

so I'm very disappointed that that's happened, but I guess you

can call it a good problem to have-to have these two heavy projects

that are occurring at the same time, so it's pure schedule-situation

that was unexpected and unintended.

MOT: Is touring grueling for you?

LG: Yeah, it's

everything that you would expect it to be. It's filled with

excitement, since it's the first time for me-filled with huge

excitement, loved doing the stuff on the stage and hearing actually

happen, and then of course there's the tiring aspects of jumping

back on the bus or changing this and going there. It is tiring,

and it is hard, but if there wasn't enough fun involved, then

nobody would do it, so it's always a combination of both.

MOT: Unrelated question: how do

you feel about Trevor Rabin's scores for movies?

LG: Yeah, I

like Trevor a great deal. I loved what he had done. In Yes he

was of course very influential and very interesting to follow,

and his scores that I see in the films are very strong. I think

he's very, very good. He's very different than I am, but I have

a lot of respect for what he does.

MOT: The reception for "Deeper" has been

phenomenal.

LG: Yes, it's a great sign to see that. That's only

fair as well for the record as a whole, and it's hard to take

a new song on tour, of course, and that one everybody seems

to just grasp it right away. I think it's just slow enough,

and it has that long epic build that's a Yes thing to do, so

you have the chance to absorb it. I think "Don't Go" is more

of a radio hit, and I think it's short enough, and I think it's

just a little harder to grasp in a live situation. It's one

of those things you need to hear a little more of from the record,

but it's working as well.

MOT:

You're fairly satisfied with the results on the album?

LG: Oh,

very much. I mean, we're still, I assume, tweaking a few last

things on the mixes. I've put in my mix notes to the band and

everyone, for what it's worth, but overall I'm completely thrilled

with it, and the orchestra's balanced just right for the scope

of what the songs are. Yeah, I'm thrilled with it. I think it's

going to be a great record.

|